Download PDF of this full issue: v47n1.pdf (28.5 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v47n1.pdf (28.5 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=3425

Download PDF of this full issue: v47n1.pdf (28.5 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v47n1.pdf (28.5 MB) |

A buddy killed, an inability to do something about it, the wrong war to die in, the chain of command and a conflict in MOS (Military Operational Specialty) all converge in my memory of my part of the American war in Vietnam. Upon being drafted after a BA from college, blind-sided by Nixon's canceled deferment for graduate school in the spring of 1968 (Speech and Drama, heavy on the Acting, no use to the Army, I thought), I landed at Bien Hoa and was deployed at Dong Tam in the Mekong Delta as a helicopter maintenance, my MOS. I knew it was the wrong war to die in because I realized right away we were an army of occupation. I mean you couldn't miss it: no front line, civilians intermixed with operations, a vast network of paved roads, equipment up the wazoo and intimate connections with the Vietnamese civilians; they did my wash, kept the hootch clean and they could party in town. I felt like a Nazi in France in 1942. I had too much education for this American war.

|

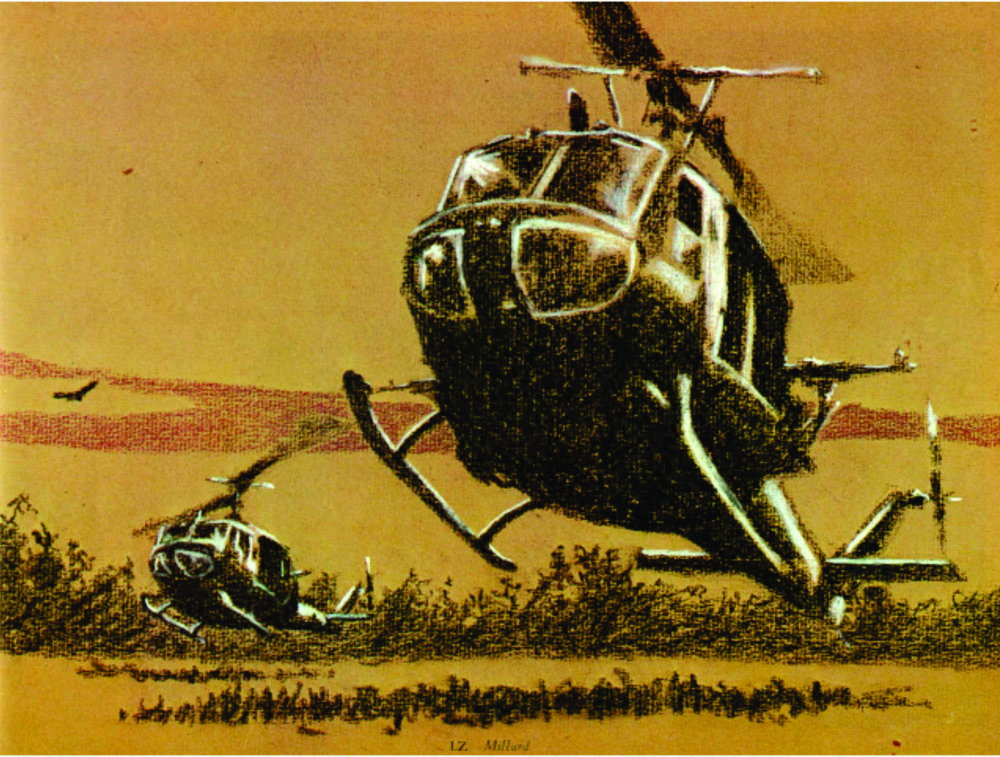

| Sketch by Steve Millard. |

I had a safe MOS, helicopter maintenance, which was better than infantry for the risk. I had the cutest helicopter in the Goddamn Army, a LOCH (for Light Observation Combat Helicopter). I trained at Ft. Eustis in Norfolk, Virginia in two months of AIT, I loved fixing that little sucker. It was like an armed toy, like the M15 we carried aboard: a mini-gun on the side and grenades you could throw down on people. And the danger and thrill of flying in a bee. No metaphor intended and it was a tactic that worked to save many a soldiers' life: the pilot, the crew chief/gunner/co-pilot in the front seats and in the back, often, a wounded soldier sprawled on the floor with an attending medic. It could land in tight spaces and get out quick. And it was an efficient weapon in league with the Cobra gunship, its main combat mission. The Cobra looked like a rocket ship and it dives raining explosive rockets on enemy targets spotted and directed by the low flying LOCH. The LOCH buzzed around about a hundred feet off the ground while the Cobra waited at a thousand feet to be called in by the LOCH when we spotted signs of a target; then, the bee would circle around, after the Cobra rocket hell, and strafe the target with its mini-gun firing fifty caliber bullets at four rounds a second and circle around again, slower, to count the kills. And sometimes land to confirm kills. All the pilots and gunners were having fun. And, I didn't have to do it, just keep my little bees running. I had read Orwell's "1984" and our shooting from helicopters at combatants and some civilians mixed in was eerily similar. I fixed them but didn't have to kill.

All that would change when the third squadron of seventeenth battalion air cavalry moved from the Mekong up closer to Saigon at Diem to fly the parrot's peak area and no longer in support of the ninth infantry division who stayed in the Delta. No more wounded soldiers and the crew chiefs were relieved not to have to clean up the pools of blood, guts, and brain from the back any more. We were exclusively flying missions with the Cobra helicopters, the hunter killer teams, close to the Cambodian border and where the North Vietnam army were gathering force. And close to Saigon, the ultimate party town of the occupation forces.

And my MOS changed as well. I was Specialist Fifth class by now and head of the maintenance team for the LOCH's of the Squadron. The old man moved up to Colonel, skipping a rank because of our success and we all gained rank fast. I sent most of my money home to my wife in preparation for graduate school, accepted at a fine university and I planned to have a child and wrote her: death all around makes you think that way. So, a new old man (commander of a squadron), a major, and new rules: a specialist is not a command rank so I was replaced by a lifer staff sergeant who didn't know his ass from fixing helicopters!

I went to my officers - pilots were all officers and we draftees and enlisted worked for them under such mutual respect as life depended on, first name basis - and said I can't work for this ignorant sergeant lifer asshole. They understood and transferred me to the flight line and I went into training to be a crew chief.

I thought I'd been saved, but soon was to find out that a crew chief meant that I had to fly, co-pilot, and shoot people. I was terrible at it, not because I had pangs of conscience, but I got extreme air sickness. Flying around in a bee, jerking up and down, banking around at 150 mph to strafe targets made me vomit all over the interior of my helmet, on my flight suit, the cabin, and my pilot. After two weeks of trying I was gratefully grounded to become assistant line chief. My best buddy was the real line chief so we made a good team and there was a step up of missions. He was also a drama student and we knew plays and Broadway shows and were joined by a new pilot who had actually seen Broadway shows.

The new warrant officer was tall, golden skinned, a Black Boston Brahman, with such an outgoing personality that he was endeared by B company of 3rd Squadron of the 17th Air Cavalry. And officers loved to fly and shoot bad guys. The war in Vietnam was won by the spring of 1970 and casualties were down as Nixon's bombing went up and the Cambodian invasion was imminent. The deployment was half a million military personnel in country and new college graduates, like our new ebony LOCH pilot, filled the ranks with a thrill for the job. Back home the economy was tanking and so I considered myself lucky to be making $800 a month towards school and looking forward to the GI Bill and even a family. The officers had better salaries and similar plans. We were making a living; armed flying was a nine to five job, with lunch break, and the target was hiding in the ground. All the pilots and their gunners had to do was move quick, look for trail signs or gaps in the Agent Orange sprayed jungle and bombed out crater landscaped terrain below and clean up.

Tom arrived about noon on the flight line. I had one LOCH left and all the other choppers had gone hunting since first light. After inspecting the work done by maintenance, they had just rolled it out from the hanger, I wrote in the flight log "clear for takeoff" and was ready to go back to my hootch and catch some z's when I heard Tom singing, "This is our once a year day, once a year day..."

"The Pajama Game, Adler and Ross, late 50s. You couldn't have seen it."

"My parents took me; I was ten. My third Broadway show."

"I was stuck with Doris Day in the movies and then I played the Salesman for our amateur group."

"The Salesman?"

"Tiny part but I got to sing all the chorus parts and dance close in Fernando's Hide-Away."

"Good for you Martin. Is she ready to fly?"

"Spick and span. New engine. After start, I'll need to look at it for leaks."

"Don't you trust 'em."

"Sure, I trained 'em well before that sergeant showed up. It's just regs."

"Always a stickler for regulations. That's why I like you, not just cause you know Broadway."

"Speaking of which, how come you're here so late and going up alone? That's against regs."

"Well, you know what the new old man says every morning briefing 'All aircraft up all the time!'"

"No, I'm here on the flight prepping choppers like all enlisted. Does he really say that, 'aircraft?'

"Yeah, he's from the chain, he commands men and this his first squadron, no experience and he wants his full bird. And the maintenance sergeant called this chopper in as soon as it was fixed."

"Good ol' chain of command, the sergeant wants another rocker and major wants to be colonel. But hold on, you don't have a gunner. Regs say you have to have a spotter.

"I don't mind, it's just a mission for road construction survey, and you know I like to fly."

"I hate it, makes me sick."

"Are you sure? I mean it's not a combat mission and I'll take it real slow. You're such a one for regs now."

"Naw, I'd just slow you down and there's no helmet or flight suit out here. I'd have to go all the back to base and the old man screaming at the delay. Does he know you're flying alone?"

"Oh yeah, all the co-pilots and gunners are up, there's only one 'aircraft' left and one pilot and I..."

"Love to fly (cutting him off) singing, "This I know of you / nothing more / gently your eyes look back on mine, surely you heard me say..."

"Rogers and Hammerstein, Flower Drum Song."

"Right, we're even. I'll get the charger."

I hooked the chopper into the charger while Tom saddled up and started the turbine. It spit a little but it's brand new and whirred fine. I went back behind, squatted down and scanned the asphalt for leaks. Clean. I took one last look, shut the engine doors, pulled out the charger, wheeled it clear, stood clear of the LOCH and gave the thumbs up sign and he returned it, and waved. I waved back. He took her straight up then banked to the right. I watched until he disappeared beyond the trees.

I never saw him again.

Tom was shot down by a hand-held rocket in a blaze of exploding fire. The memorial service for a fallen air cavalry officer was kind of corny. There were black boots surrounded by a scarf synched with the battalion emblem topped with a black cavalry hat on display in front of the lectern on a platform. Years later, when I saw "Apocalypse Now" and the part played by Robert Duval going into battle in our dress outfit, I was appalled by the inaccuracy. And attacking a peaceful village of civilians. We never did that. We honored the free fire zones set up by command and stuck with it. The movie stank in my opinion. In the battalion chapel, the officers were crying to a man because Tom was loved and no one was listening to the platitudes of the preacher; he finally just shut up. The major was not there, for he had been removed from command for violating regulations by sending a lone pilot up without a gunner/co-pilot who might have spotted the bad guy and saved both lives. That should have been me, but I was lousy at that MOS. Had I gone on that flight, we would probably both be on The Wall instead of just Tom; going slow and singing show tunes as we died.

Martin Treat is a retired Teacher and Actor living in Manhattan. He is currently Suffering from the effects of Agent Orange with Motor Neuron Disease. He has been a member of VVAW since 1975.