Download PDF of this full issue: v47n2.pdf (94.2 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v47n2.pdf (94.2 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=3513

Download PDF of this full issue: v47n2.pdf (94.2 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v47n2.pdf (94.2 MB) |

I was so very pleased to see Scognamilio appear on Hill 29 in the spring of 1968 even if he was not trained to do my job. The First Sergeant had escorted him to our residential bunker and told me to make this guy a tank driver.

|

Yes, I was short and Scognamilio was my replacement. Fortunately for him he was two months early and I had plenty of time to teach him how to be the driver of an M48A3 tank. 52 tons of ugly beauty, which, I promised, would keep him alive for 12 months.

It did not. Thirty hours after letting go of that tank I was in Chu Lai processing out of the squadron when the word reached the rear that A-35 had detonated an exceptionally large land mine. There were no survivors.

At Cam Ranh Bay I waded into the warm ocean and cried into the waters.

The flight home across the Pacific was not as euphoric as it might have been.

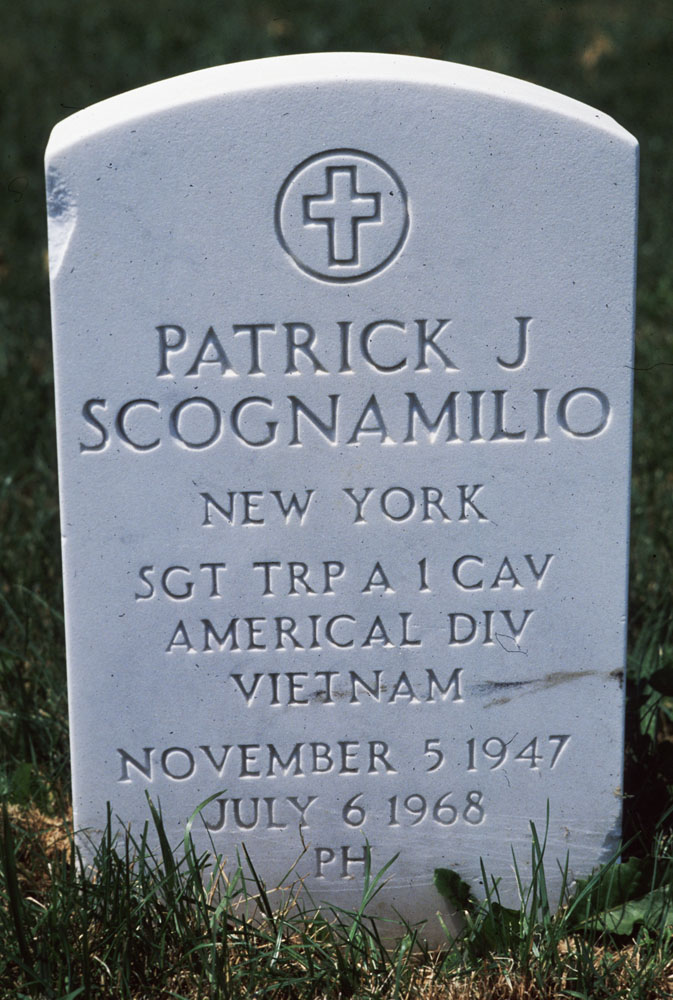

Scognamilio and I were both from New York City so I was able to contact his family and later attend the funeral. A funeral delayed a month after his death as he was listed as "missing in action."

The mental picture the family had constructed from what the Army told them was of a tank found in the jungle with its engine idling and the crew having wandered off. There was no jungle; no idling tank; no curious, dismounted crew following suspicious footprints. Reality was a column of a traumatized armored cavalry platoon with its lead vehicle gone in a fireball.

Later, they would find nearby a broken open 1,000-pound bombshell that had failed to explode on impact. Copious peanut shells suggested some enterprising VC had scrapped all the explosives out of it and ate peanuts as they worked.

Still on active duty, I travelled to the Pentagon. After much walking through endless corridors I finally found a kindly major who had Scognamilio's folder open on his desk. All they had that they were sure was Scognamilio were his eyeglasses and his left hand. I politely but firmly told the major it was time.

The Italian funeral in Brooklyn was about what I expected complete with grandma trying to open the casket. Many tears.

The next year I returned to college where Scognamilio would visit in my dreams. He was working on the tank's track and wanted my help with the maintenance. I knew what he really wanted.

So, in May of 1970 I bought a ticket to Saigon on Pan Am. I managed to get myself accredited with MACV as a photojournalist, which gave me the run of the war, and, as a noncombatant, a prohibition from touching any weaponry.

|

In July, a chopper dropped me off next to an armored column in the field, A Troop, First Squadron, First Cavalry, which was the very same troop in which I had served two years previously. The captain altered their route at my request and the multi-piece wreck of A-35 came into view.

In 1968, our practice was to ride on the top of the turret until small arms fire was directed at us since we were more fearful of land mines than of bullets. The driver, down in the hull, did not have that option. So, when A-35 detonated that mine the turret crew was blown clear, although dead. The inverted hull, minus the turret, burned all day and prevented the platoon from retrieving his body. Lingering in that area after nightfall seemed unwise so the LT had the platoon move on.

No one went back for Scognamilio until two years and a few days had passed. We found most of him behind the steering wheel of the tank. His dog tags were in his bootlaces so we knew it was he. Since there was a grave on Long Island with his name on it I did not want to inflict another funeral on the family. Maybe I made the wrong choice but the cavalry troopers dug a resting place in the good earth for him and the many fragments of the other crew members found scattered about.

I knew that someday the war would end and the A-35 with him in it would be hauled off to China to be melted down into dishwashers or whatever. I did not want that indignity inflicted upon my friend.

In the past eleven years, I have traveled to Vietnam ten times. I have established relationships with Vietnamese and made myself useful as a photographer to various NGOs. More meaningful has been the Dragoon Scholarship Fund I established for poor children in one of the many rice-farming villages Scognamilio and I "visited" in 1968. Primary and secondary education is not free in Vietnam, but as of September 2017, fifty children are attending school thanks to the generosity of both veterans of that war and kindly others.

In conjunction with the Dragoon Fund there is an annual bit of organized silliness that involves chocolate. Lots of it in both solid and creamy formats. I have also told the children of An Son about the famous humanoids of the Pacific Northwest forests of my homeland and their interest in the happiness of human children. Races are held in honor of Ông Chân To (Mr. Foot Big) with the winning teams being awarded the traditional red envelope with three crisp US $2 bills (which are considered very lucky in Vietnam.)

All of these activities have helped put Patrick Scognamilio to rest and he doesn't visit my dreams anymore.

Richard Brummett has been a tank driver, cab driver, photographer, and postmaster. He is a life member of VVAW and lives in Bellingham, Washington.

Children of Vietnam Dragoon Scholarship Fund