Download PDF of this full issue: v48n1.pdf (140.6 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v48n1.pdf (140.6 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=3567

Download PDF of this full issue: v48n1.pdf (140.6 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v48n1.pdf (140.6 MB) |

The following is an excerpt from Suzanne Gordon's forthcoming book Wounds of War: How the VA Delivers Health, Healing, and Hope to the Nation's Veterans.

|

|

Suzanne Gordon speaking at the Right to Heal panel, March 1, 2018. |

To expect that homeless, low-income, or mentally ill veterans with multiple chronic conditions—or the stressed-out family members who care for them—will be able to navigate the medical-industrial complex outside the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), on their own, is a cruel and irresponsible fantasy.

Magical thinking about Choice most dramatically obscures its bottom line. Since Choice was launched in 2014, on a limited basis to reduce appointment days and long trips to VA facilities, the program has had $2 billion in cost overruns. Now President Trump says his goal is increasing the percentage of patients getting some care outside the VHA from 30 to 90 percent. Unlimited outsourcing will bankrupt the VA, first eroding and then eliminating the VHA as a public option for veterans. Choice program legislation, in all its proposed forms, never includes supplemental funding to pay for private-sector care, which will cost far more. That omission is intentional because, according to one estimate obtained by the Commission on Care, if 60 percent of all eligible veterans were treated outside the VHA, the cost of their care would quadruple.

Since that assessment, the San Francisco-based advocacy group Fighting for Veterans Health Care (FFVHC - www.ffvhc.org), which I helped form, has carefully analyzed every congressional proposal to expand veterans' care in the private sector. In each bill, every dollar spent on outsourcing is absorbed by the VHA's own operating budget. No additional funds are earmarked for the exemplary in-house services showcased in Secretary Shulkin's own book, "Best Care Everywhere". As the FFVHC predicts, the result of expanded outsourcing will be cuts in VHA programs, staff, and veterans' benefit coverage.

While Congress was still debating the future of Choice, Shulkin was already trying to cover its mounting deficits and VHA operating budget shortfalls by shifting nearly a billion dollars away from existing programs. As I reported in American Prospect, he floated the idea of shuttering ten Patient Safety Centers of Inquiry (PSCI). These VHA facilities have developed innovative methods of reducing suicide and other forms of self-harm, now widely copied outside the veterans' health care system. Only after Senator Bernie Sanders called Shulkin personally, and nationally known patient safety experts like Berwick and Lucian Leape wrote personal letters of protest, did the secretary abandon (for now) any PSCI closing plans. Unfortunately, others, with PSCI's at risk in their own states, failed to respond, including Senator Elizabeth Warren and Congressman Seth Moulton, a veteran himself.

Then, in October 2017, the VA leadership changed course again, issuing a memo giving medical center directors the green light to shift money from earmarked programs to fund general operations at the local level. This move threatened $265 million allocated for the HUD-VASH program, in which social workers find housing for homeless veterans. Other funding at risk included $30 million originally budgeted for mental health initiatives and $21 million for staff assisting Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in their transition back to civilian life.

The authorized funding shifts were expected to impact suicide prevention efforts (notwithstanding Shulkin's claim that they were a top personal priority), spinal cord injury rehabilitation programs, and post-amputation care for victims of disabling injuries on and off the battlefield. About $26 million allocated to Mental Illness Research Education and Clinic Centers was targeted for trimming. These centers do pioneering research on the causes and treatment of mental disorders and translate this knowledge into new clinical practice with veterans. Almost $23 million in funding for VHA occupational health and safety programs became uncertain. This led to cancellation of some already scheduled staff training on how to lift patients safely in hospital and nursing home beds and better handle those who are disruptive. In similar jeopardy were in-house programs to prevent workplace harassment or violence among coworkers, a not well-timed cut in the post-Harvey Weinstein era.

After much prodding from female veterans and groups like IAVA, the VHA had launched—just prior to Shulkin's directive regarding earmarked programs—a $6 million women's health initiative. Its advocates now had to scramble to keep it afloat. As the impact of other program defunding was felt across the country—for example, among homeless veterans—both national VSOs and local advocates like Michael Blecker at Swords to Plowshares registered strong objections. Thankfully, the VA was forced to backtrack on its curtailment of services to the homeless.

As the federal government, overall, is deprived of future revenue because of 2017 Trump tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy, conservatives in Congress will make a renewed effort, while they control the House and/or Senate, to curb all "entitlement programs." Veterans will not be immune from this trend, when the debate about the future of Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security resurfaces under Trump. And the potential for VHA eligibility being curtailed or veterans being pitted against other federal benefit recipients is very great.

|

The VHA's emerging "death by a thousand cuts" requires official camouflage and rationales designed to mollify potential critics. Secretary Shulkin, for example, frequently implied that the agency can best survive and thrive by reorienting itself toward "foundational services" or, in some iterations, its "core mission" (i.e., caring for combat veterans). In his testimony at a February 15th hearing of the House Committee on Veterans Affairs, Shulkin argued that the VA should focus only on what he called "foundational services" like primary care, mental health treatment, geriatrics, and extended rehabilitation. A wide range of other services—cardiology, oncology, urology, etc.—would no longer be integrated or comprehensive. Instead, they would be turned over to private doctors and hospitals. This is, of course, precisely what private sector hospitals are angling for. They don't want to deal with the real wounds of war that require labor intensive, chronic disease management or caring for suicidal or homeless veterans. They want to siphon off the high cost, episodic treatments like colonoscopies or hip replacements. What this strategy ignores is the fact that the unique strength of the VHA, as documented in this book, lies in its unmatched system of integrated care. Plus, it threatens to pit one category of patient against another, undermining the unusual sense of solidarity and community among veterans served by the VHA. If the agency no longer treated those without battlefield wounds, who represent about two-thirds of its current patient population, where would such an institutional reorientation leave many men and women profiled in this book?

What would it mean for sixty-year-old Susi Black, still hobbling one-legged through life, if she were deprived of VHA help because she's not a real wounded warrior? Or thirty-nine-year-old Demond Wilson, who would be literally flat on his back and dependent on local social service agencies or private charity without VHA assistance? Josh Oakley, who never left the continental United States while on active duty, would, according to his own account, be dead if it were not for VHA intervention. How would Norissa McLorin be faring if she became ineligible for military sexual trauma treatment because she was sexually assaulted, stateside, at a base in South Carolina with no less trauma than if the attack by a fellow soldier had occurred in the Sunni Triangle?

All these former service members have medical problems acquired or exacerbated during their military service. Even when those conditions developed long afterward, they were promised health coverage, if needed, when they signed up and made their decision to serve. Should funding of that commitment be withdrawn now? Or, worse yet, should millions of dollars that could be spent on direct care be siphoned off instead through the process of contracting out?

Already, the opportunities for Choice program waste, fraud, and abuse have been well documented. In the future, they may only increase, at further expense to the US taxpayer. In September 2017, for example, the inspector general of the Department of Veterans Affairs sent Shulkin a report on payments to TriWest and Health Net, whose combined reimbursement totaled $649 million. Between 2014 and 2017, the VA contracted with these third-party administrators to set up networks of Choice-approved providers, schedule appointments for veterans, collect medical documentation, and pay provider-submitted bills. The IG's audits found much evidence of medical claims paid more than once, payments that didn't use the correct Medicare or contract adjusted rate, and overpayments to Health Net and TriWest totaling nearly $89 million over a two-year period. Despite this unpromising start with Choice claims processing, Shulkin proceeded to hold secret discussions about merging Choice with the military's Tricare insurance program, which covers active-duty personnel and their families and was formerly administered by TriWest.

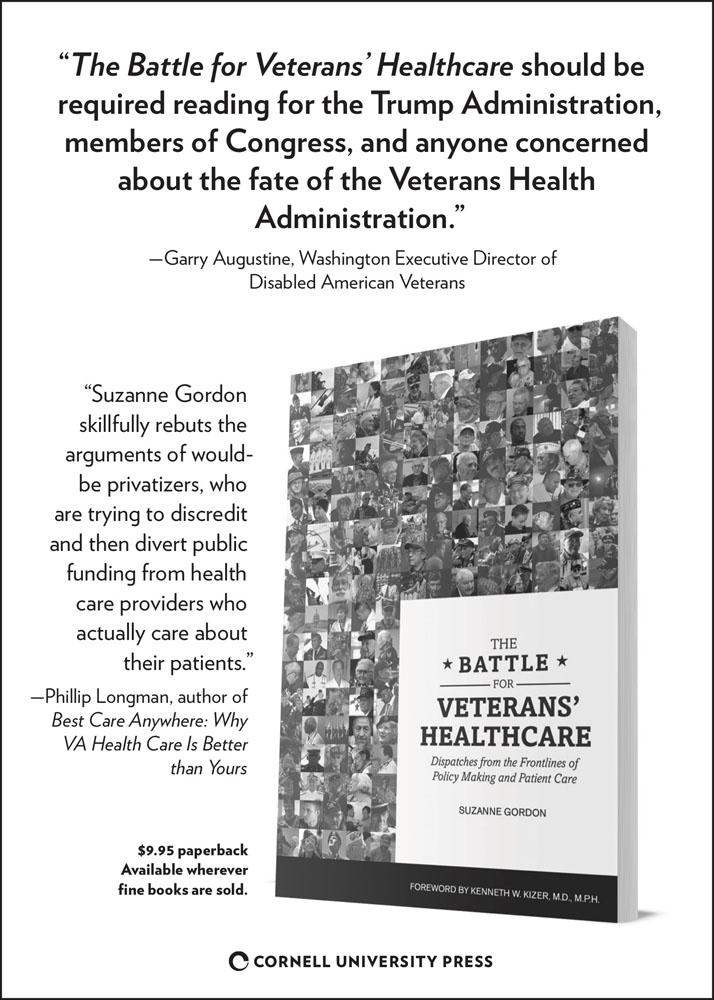

Suzanne Gordon is the author of The Battle for Veterans Healthcare: Dispatches from the Frontlines of Policy Making and Patient Care. Her latest book, Wounds of War: How the VA Delivers Health, Healing, and Hope to the Nation's Veterans will be published in November by Cornell University Press.