Download PDF of this full issue: v48n2.pdf (20 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v48n2.pdf (20 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=3679

Download PDF of this full issue: v48n2.pdf (20 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v48n2.pdf (20 MB) |

Pre-dawn dew soaked through my sandals as I took the more direct route from the campground to the meditation hall across a wide field of grass. A playful déjà vu sensation enveloped me as I recalled cutting across yards as a child in contrast to my adult habit of staying on sidewalks. The low croak of frogs and the songs from birds and crickets welcomed me. As I neared a tree line, the glorious chorus of mating songs from cicadas looking for love after their seventeen-year sojourn underground reminded me of my longtime love of their calls and amazement of their life cycle. Funny how my Vietnam experiences resulted in a constant ringing in both ears that most resembles a cicada's song.

|

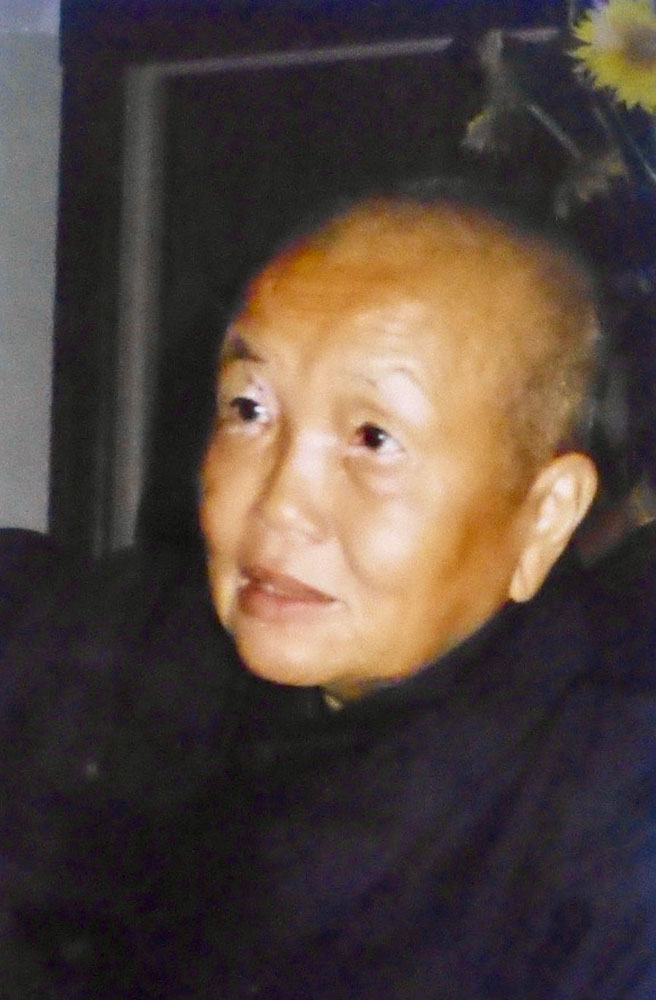

| Sister Chan Khong, a Vietnamese Buddhist nun, at a Buddhist retreat in 2003. |

A police official in Madison, Wisconsin organized this five-day retreat at the nearby Green Lake resort in August 2003 with the hope that police officers and others in public service would attend. The moment I heard of it and that Thich Nhat H nh, the Vietnamese Buddhist monk I so respected, would lead it, I felt drawn to be with a spiritual leader from the war-torn country that was the source of my moral injuries.

My tour of duty in Vietnam produced a case of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) that I now know is very typical for combat vets. At the time of the retreat, I was in my fourth month of weekly talk therapy sessions. My psychotherapist (who had also served in Vietnam) and, later, the VA agreed that I was partially disabled due to combat-induced PTSD.

I walked across the field that first morning towards the meditation hall for Thich Nhat H nh's (or Thay, "teacher" in Vietnamese) dharma talk. A large banner on the wall to my right read, "i have arrived i am home." I wondered if the lower case "i" was to remind us of the ego's link to craving and the Buddha's lesson that grasping is the source of suffering.

In slow motion, Thay poured water into a glass, moved it two-handed to his lips, and smelled it before he sipped. With a smile and a soft voice muffled by a thick Vietnamese accent, he advised that mindful observation is the "element which nourishes the tree of understanding, and compassion and love are the most beautiful flowers."

Thay's co-leader, Sister Chan Khong, was highly respected for her involvement in Southeast Asian relief efforts for refugees and war victims since the 1960s. I wondered how she was able to maintain a near constant smile after experiencing a decade of war. I requested a consultation with her mentioning my struggle with PTSD, and I felt honored when she agreed.

When we met, I didn't know how to start. With a soft reassuring voice, she suggested, "Start with the worst." I struggled with an instantly dry mouth and got out only three words: "We killed children..." I choked on my tears as my face scrunched. I told her an abbreviated version of one war story—my first experience with the atrocity that is war.

From a guard tower about thirty yards away, I watched as two young boys tried to run away after successfully setting off a homemade bomb that killed three fellow Marines. With a well-practiced calm, I flipped the lever on my M16 from SAFE to AUTO. But before I could finish squeezing off a three-round burst, the machine gunner in the adjacent guard tower opened up. He had a clear shot at less than twenty yards as the two boys ran directly toward him. The fine dust danced a three-step toward the taller boy. The next burst ripped through his right thigh, belly, and chest and sent him reeling. An instant later, after a minute adjustment by the gunner, three more lead slugs bore clean through the other boy's little chest. He collapsed abruptly in a heap.

After a long pause, Sister Khong said that if I practiced mindfulness, I could look deeply into the nature of myself and touch my suffering. I could learn to live with my fear, my doubts, my confusion, my guilt, and my anger. My task, she said, was to dwell in those places like still water. But if I didn't practice mindfulness, I would continue to live in forgetfulness, controlled by my suffering. She offered a final suggestion: "I try to give joy to one person in the morning and reduce the suffering of one person in the afternoon by deep listening. Deep compassion."

I thanked the kindly nun. Like the initial sensation in an elevator going down, the gravity of my past had less of a drag on me.

Thirty-three years after the war, I began to feel like i had arrived. i was home.

After experiencing combat in numerous search-and-destroy missions in Vietnam, Michael published a memoir of his experiences in 2001, Fire in the Hole: A Mortarman in Vietnam.