|

Coming Out of The Footlocker As A Military DependentBy Herb MintzAs a son of an NCO who served more than 20 years in the Armed Forces, I was a military dependent for almost sixteen years. A military dependent is the spouse or child of active duty and/or retired military personnel who serve or have served in the Armed Forces. Dependents occupy the home front, the perimeter inside the perimeter.

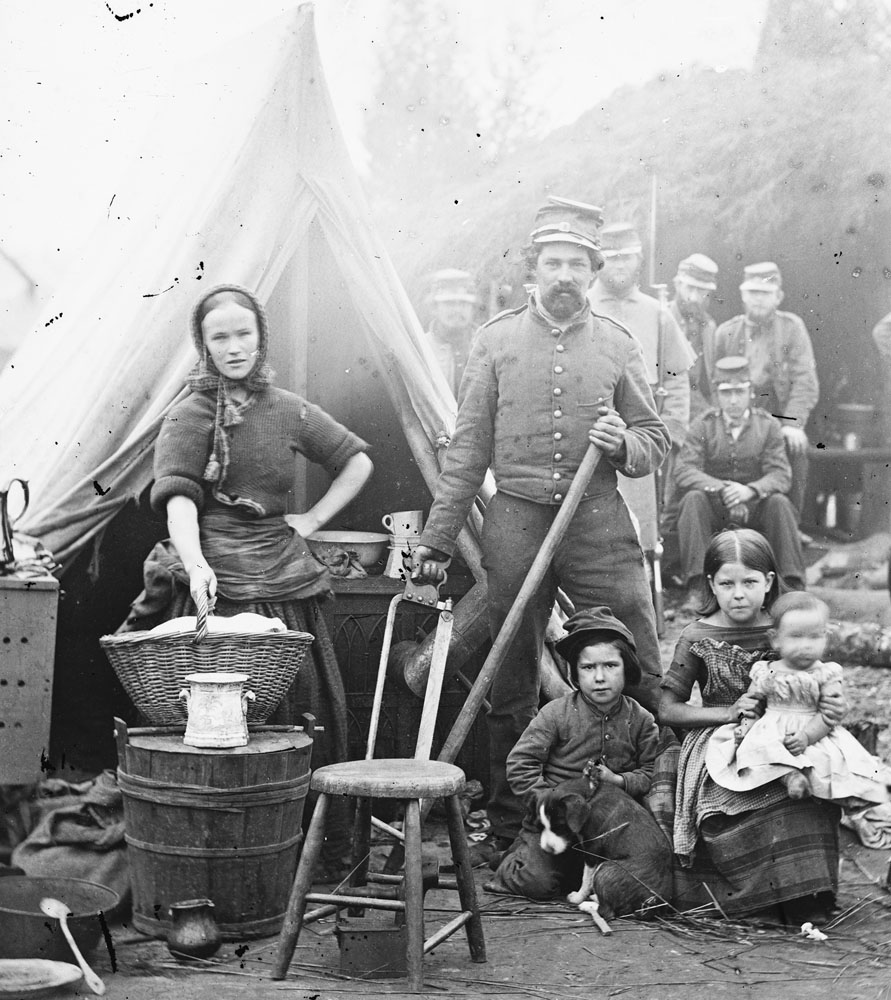

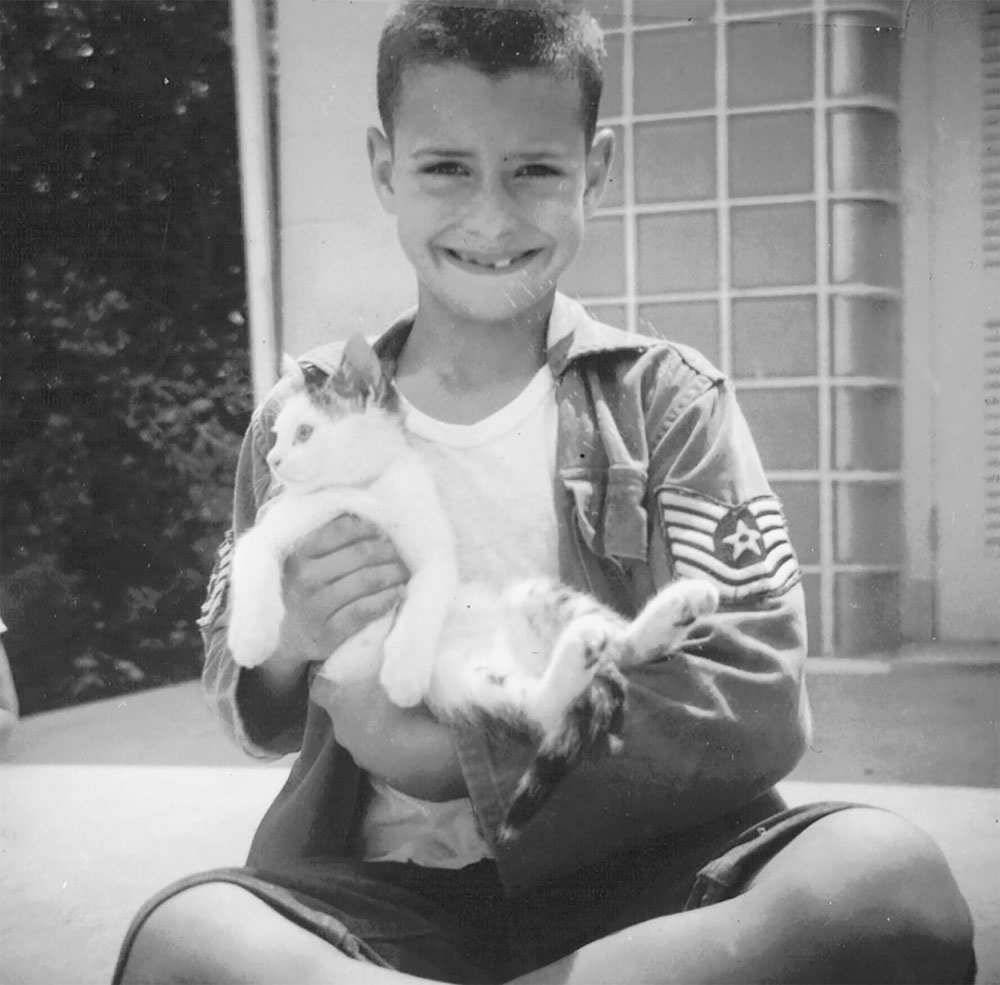

My Dad received a notice for military service after the end of WWII during a peacetime draft. On July 1, 1948, he joined the Air Force. After boot camp, he was assigned to Offutt AFB in Bellevue, Nebraska, the Headquarters of the Strategic Air Command. When my Dad's initial enlistment was about to end in 1951, he had a chance to exit the Air Force honorably, but, due to the Korean War, he "was frozen" (his words) in the Air Force for an additional twelve month extension of his first three year enlistment and another full re-enlistment of three years beginning in 1952. In 1953, I was born into a military family, inside a military installation, Offutt AFB, as a military dependent. I didn't know it but I was born into larger history of military dependency, The Camp Follower (see photo). Camp Followers were, for the most part, the children and wives of male soldiers. From camp to camp, they provided multiple services for their male soldiers engaged in military service. The Air Force, during my years as a dependent, no longer required many of the historical services to be provided solely by a family member for my father-soldier, but for the most part, we did follow my Dad from base to base. My Dad's served as an airman from July 1948 to October 1968. His tours of duty, without my military family, included, Yokota AFB, Japan (1956-57), Osan AFB, South Korea (1960-62) and Tan Son Nhut AFB, Saigon, South Vietnam (1967-68). He was "in country" during the January 1968 Tet Offensive. After Vietnam, I preferred to call my Dad a soldier. I followed my Dad's path between and inside his stateside duty stations: Offutt AFB (1953-56); Lackland-Kelly AFB, San Antonio, Texas (1956-59); Donaldson AFB, Greenville, SC (1960-62); Truax AFB, Madison, WI (1962-64); Ent AFB, Colorado Springs, CO (1964-67); and Wilmington, NC, while my Dad was stationed at Tan Son Nhut AFB, South Vietnam (1967-68) and until he terminated his active service at Seymour Johnson AFB, in Goldsboro, NC, in 1968. A common experience of the dependent is the transfer every two to three years to a new duty station for the career soldier and the absentee parent-soldier. My Dad's first transfer occurred in March 1956. He was sent to Japan. My dependent family did not follow him there since my Mom's parents were both ill. This was the first time that my Dad was absent from the home front for more than a year. In 1957, my Dad-soldier, returned to Offutt AFB from Yokota AFB in Japan and received his new orders for Lackland-Kelly AFB in San Antonio. With any duty transfer, housing is paramount. My military family moved into NCO housing at 40 Venus Street, Lackland-Kelly Homes. Our unit was built in 1940 and was located on the periphery of the base. I first experienced the concept of TDY while my Dad was stationed at Lackland-Kelly. He received his orders one day and was gone the next but only for short periods of time. In 1959, my Dad-soldier, received his new orders for Donaldson AFB in Greenville, SC. Mom told me that there would be military housing for us. There wasn't. After many days in a motel, my military family moved into a small house in an established civilian neighborhood and then into an isolated cinder block house in the countryside near Piedmont, SC. In 1960, my Dad was transferred to Osan AFB in South Korea. Another aspect of the military dependent experience is that the vast majority of the time there are no family relatives living nearby. The only relative, according to my Dad, who resided nearby, was my Uncle Sam. On occasions when my Dad-soldier was absent, my military family could have use a little help from my Uncle Sam but it never materialized. Another defining feature of the military dependent is the changing of schools after moving. In 15.5 years, up to the eighth grade, I attended eleven different schools. Dad returned to Donaldson in early 1962 and shortly thereafter, he received new orders to transfer to Truax AFB in Madison, Wisconsin by March 1962. This would also be the first time I left school before the term ended. There was no military housing for us. My Dad rented a small house just outside of the base on the very eastern edge of the Madison city limits. In late 1962, my military family of six did move to 926 Mitchell Street, a one-story, two bedroom, one bath duplex in the new Capehart Military Housing on the western edge of Sun Prairie, WI. We shared one half of a rectangular building with another NCO military family whom I never spoke to or got to know. There were two doors into our unit and a small asphalt slab where a car could be parked. For a long time, there was no grass or weeds just dirt that surrounded the duplex. After the first good rain, water leaked into the basement. My first experience of class in the military happened there. Through our backyard and across a street and up a slight hill was a small cluster of Officer's houses. Each unit came with an attached single car garage and a large lot. Separated by less than 150 feet, the distance in terms of my place in the military hierarchy was clear. The NCO dependent was at the bottom of the military hierarchy. During our stay in Capehart, my Mom began to work outside of the home. I learned from her that my Dad's income wasn't enough to support our military family. Another feature; in my 5th grade class, the label "military brat" was directed at me. Hearing that for the first time caught me off-guard. No meaning associated with that label described my meager and marginal existence in the Nation's internal perimeter. The attitude embodied in that label confirmed just how little the civilian sphere knew about my diminutive and marginal social status as a military dependent. Later, when I was much older, I could see how the label "military brat" might have an important public relations use. The label disguised the reality of the lower-class status of the NCO dependent. As a gross overvaluation of the status of a dependent, "bratdom" acted as a deterrent to the serious questions that might be raised if the military dependent situation was seriously scrutinized in social, psychological or economic terms. My last friendship with another male dependent occurred in Capehart. My Dad received his orders in 1964 to transfer to Ent AFB in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Rodney, on his bicycle, followed our car out of Capehart, waving one of his arms upward, yelling to me in the car, "Don't go, don't go." I still remember how our car slowly pulled away from him as he furiously pedaled after us. Military housing wasn't available when we arrived at Ent. Since Ent was a small downtown AFB, the only available site with housing was an Army post, Fort Carson, located about 10 miles south of the city. And that was temporary housing only. I attended Stratton Elementary School. The school cafeteria lunch program served food from containers labeled, government surplus. My military family shopped exclusively for food at the base commissary as it was what we could afford. I didn't understand why civilians would chose to eat a similar kind of food. After living in several rentals for about a year, Mom and Dad, without any notice, bought a home in a civilian neighborhood in Colorado Springs in late 1964. Access to this level of the civilian life came with a price. As soon as we moved into our first home, Mom and I both began to work for wages outside the home. I was in the seventh grade. There was no choice. There was no overtime or extra work available to NCOs and my military family needed the money. Three incomes helped to hold it together financially in our new role in the consumer society. The discipline I experienced as a military dependent wasn't altered during my integration into this civilian sphere. I still had to shine my shoes, look neat and tidy, get a haircut every week, scrub my head and body clean, conduct my official duties at home without a fuss, listen to every word my Dad said and of course, show deference to Uncle Sam, our only local relative I never met. My experience did include obedience to authority, conformity to military norms and a slow baked-in underdeveloped awareness of civil liberties, civil rights and citizen activism as a result of our separate lifestyle. In my Dad's house, as far as I can remember, there was no possibility of dissent, acting or speaking out on any issue of the day. What did my Dad and my military family talk about together? The safe stuff, religion, sports, our tasks, our duties and the goodness of work. No politics, no popular culture or TV shows, no policy issues, no political parties or no current events. We didn't even talk about the Air Force! You never knew who was listening or what subject matter might get you into trouble with the military authorities. And that lead to the great fear of my military family—the Black Mark in the personnel file of my Dad, the soldier. A Black Mark was a sign of shameful behavior or behavior subject to discipline or punishment and meant a possible loss of income or opportunities to advance in rank. In the past, our housing was substandard and my Dad's income was already low and so there was much to lose. In early 1967, after almost two years in a civilian sphere, my Dad received orders to report to Tan Son Nhut Air Force Base in Saigon, South Vietnam. At first, to me and my military family soon to be without my Dad-soldier, well, we knew another transfer was coming, sooner or later. My immediate thought was how will we manage. My Mom informed me that my Dad thought he would be killed in South Vietnam and that we'd better off if we lived near his relatives in North Carolina. Uncle Sam, my silent relative, wasn't going to cut it while my Dad was in South Vietnam. As usual, on a given date, we packed up our things, let movers take some of those things away and then got into the car and left for Wilmington, NC. That would be the last transfer of my military family and the last site for the last 17 months of my tenure as a dependent. We stayed at his family's farm until Dad and Mom found an older rental home near a protestant church that my Dad's brother's family attended. We moved in and one day in the near future, my Dad unceremoniously departed for duty in South Vietnam. Air Force office personnel generally do not experience combat as it has been and is today portrayed in the combat film or war movie. Although my Dad's service records suggest that the vast majority of his work for the Air Force was inside a office building, during my Dad's tour in Vietnam, according to his Department of Defense military records, he acquired counterinsurgency experience. My memories of what I learned or heard about my Dad while he served in South Vietnam is limited since my Dad communicated solely with my Mom. In general, my family minus my Dad-soldier adopted a sort of business as usual attitude. That was the case early on since my family had experienced my Dad's numerous departures in the past and didn't think too much about this one. My Dad wrote every now and then. From Mom, I learned that he contracted a foot fungus, that the heat and humidity were unbearable, that he didn't like the base cafeteria food and was saving money in a special account that earned 10% interest. Since my military family didn't watch the TV or listen to the radio for news updates, Mom was the only source of information that came straight from my Dad during the January 1968 Tet Offensive. One day, he called to say he was OK and that was that. 1969 was the first year of my life as a civilian. In 1971, I was required by law to register with the Selective Service System. I was classified 1-A shortly thereafter. By that time, most people I knew, even in conservative Wilmington had doubts about the US involvement in the Vietnam war. When I entered the university in September 1971 voting rights, civil rights, women's rights, gay and lesbian rights, black liberation and in particular, the question of the Nation's involvement in the Vietnam War were front and center. I encountered those social movements and social experiences not only as an ex-military dependent but as someone who was willing to struggle to comprehend the issues of the day. There were many soldiers returning from Vietnam that were more than willing to talk about their experiences than my Dad. While attending university, I learned that the Federal government and the Pentagon had been untruthful about the role of the United States Armed Forces in the Vietnam war. Most importantly, the Gulf of Tonkin incident, the basis for US intervention into Vietnam, was a fiction. Furthermore, the government in South Vietnam was not an aspiring democratic government in need of the Nation's support but a military dictatorship, representing only a small fraction of the citizens of the country. I learned the United States had secretly supported the French government's effort to re-establishe its colonial territory in Vietnam and later refused to hold elections in South Vietnam which would have resulted in a victory for Nationalists and Communists. But that was just my first lesson in the real history of the United States military. I eventually opposed the war in Vietnam and attended rallies, protests, teach-ins and sit-ins. My silence about my past life as a dependent of nearly 16 years began when I had to face the fact that the single most important feature of my experience was that the government that paid for me, my siblings, my Mom, and my Dad, had lied to us so shamelessly and violated our trust. Herb Mintz drifted about, getting involved with community, media and labor organizations until he retired. He married and now lives in San Francisco.

|