Download PDF of this full issue: v50n1.pdf (30.8 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v50n1.pdf (30.8 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=3859

Download PDF of this full issue: v50n1.pdf (30.8 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v50n1.pdf (30.8 MB) |

Excerpt from Winter Soldiers: An Oral History of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War by Richard Stacewicz, pages 192-197.

Jan Barry (JB):When I got out of the Army, in May of 1965, [I] flew back to upstate New York and immediately came to New Jersey. There was a girl here I had been writing to and therefore decided to come to this region looking for a job. I ended up getting a job for a newspaper that I'm actually working for now, in the library.

She went to a peace demonstration either in 1965 or early 1966 in New York. I wasn't in any way interested in going to this peace demonstration. She came back. I asked what happened, and she said some news person came up and asked why she was there and she really didn't have anything much to say. I remember being mad at her. "Well, why didn't you know why you were there? Why couldn't you say why you were there? Why couldn't you say what's wrong with the war?"

At that point, my sympathies were to research what was going on. I researched everything, from reading Mao Tse-tung in the original to what's behind their side of it, and whatever else I could get my hands on. I was taking college classes on Saturday, and I took economics. I did research into our economic relationship with South Vietnam. Out of this I learned that we were, in essence, turning it into an economic colony, turning a rice-exporting region into a place [where) we sell them rice. There were lots of articles in Fortune magazine and other kinds of places about these great deals that were being done.

I talked to people. Reporters started telling me they'd go out and interview the ones just coming back from Vietnam, [in] late 1965, early 1966, from the first larger wave that went in there, and "These guys are more bitter than you are."

At one point, I ran into one of these guys, and he was extremely bitter. He was the only survivor in a unit that was wiped out. He said "Why the hell should I prop up this rotten society?" He disappeared and no one ever heard from him again.

That was the thing that propelled me to organize something, realizing that there were all these angry guys out there, so turned off from their own society that it was frightening. Somebody had to articulate why that anger was there, what that bitterness was about. I didn't know how, but I had to learn how to do that.

I remember toward the end of 1966 I had finally reached a point of frustration. I decided to move to Manhattan and start looking for more compatible people. I didn't think [of] a peace movement. There were lots of people who were asking questions. They were thinking about raising the questions. None of these questions were visible in the news media that we worked for.

Things like "Johnson Goes on Peace Parley" would be the headline. You'd read the story, and it had nothing to do with a peace parley; it was a war parley. Everything was out of a Washington perspective. Even if the reporter from the New York Times or whatever was reporting from Saigon, the story got twisted around to be a Washington perspective. You learned how to read between the lines. The editors were doubting their own reporters in Vietnam. That was very clear to me. It all added up to: The American public has no idea whatsoever of the reality. How do you convey that reality when everything seems to be closed up?

I walked into the New York Public Library main branch one day, asked for the personnel office, and said, "I'd like to work here." I took a pay cut and took the job, filing things and all the rest of the stuff.

I discovered there were all these students from all the various colleges in New York who worked there, and they were talking about something [that] was going to happen in the spring. They were so out of it. We're talking about young students who had no idea about anything. This didn't lead me to want to get involved with them until I saw an advertisement in the New York Times Book Review from the Veterans for Peace, saying, "If North Vietnam stops bombing us...we'll be ready to negotiate" or something like that. It turned the whole thing around. They weren't threatening us. "Join us, April 15th," I think it said, "at Central Park for the start of the march"—which was the first time, place, and invitation that I felt, Ah-hah, that appeals to me. I liked the way they turned the issue around, a twist on reality.

I went with a friend [and] several people from New Jersey. There was this mob scene. There was a huge number of people at Central Park, from Columbus Circle all the way back as far as you could see. One of the stories of the peace movement that still hasn't really been told was the diversity. It wasn't just this hippie image that has determined the legend. This demonstration that I'm seeing for the first time was full of families in their Sunday best and younger people. This was pre-hippie. People in 1967 still had straight, narrow ties. Look at all the civil rights people and the peace movement people of the time: suits and ties, short hair. I went there wearing a suit and tie and a raincoat.

As we're standing there wondering what to do next, there's this big cry, "Vietnam veterans to the front!" There's this huge group of disciplined people marching, wearing Veterans for Peace hats. At the beginning of this group of veterans someone had provided a banner, hoping some Vietnam veterans would show up. It said, "Vietnam Veterans Against the War." There were some guys already carrying the banner and there were some guys behind them. I just joined that group.

There were some young guys in parts of uniform, or suits and ties, and some women and children. I don't think there were more than a dozen Vietnam veterans and some family members; but behind them—which to me at the time was far more impressive—was like a regimental size, I think 2,000 guys, marching in military formation wearing Veterans for Peace hats.

When we proceeded out of the park and down through Fifth Avenue and through the various other streets, people were ready to lynch, howling and screaming and throwing things. First they see a little group of dignitaries, which apparently included Martin Luther King, Jr., Dave Dellinger, A. J. Muste, and a couple of other people carrying an American flag. They're way out there by themselves taking all this abuse. Then, there's this little band of people carrying a sign, "Vietnam Veterans Against the War." You heard this sea change in the crowd. "What is this? Is that for real? [Angry tone.] It can't even be for real. This has got to be a joke." Then behind that, this group that clearly is veterans. "What!" I mean, this isn't what they expected. "Who are these people? If they're involved, I've got to rethink my opposition to all these people, hollering and screaming at them." You literally could feel and hear a change in these sidewalk crowds. Of course, behind that came a crowd that was so huge [that] they filled up all the streets in midtown Manhattan over to the UN and blocked all the traffic. The entire plaza in front of the UN was filled. All the side streets were filled, and people were still coming.

The march on April 15, 1967, brought together numerous pacifist and leftwing organizations to form the first mass mobilization against the war. It was estimated that between 200,000 and 400,000 people marched in the rain in New York, while another 50,000 marched in San Francisco. As Charles De Benedetti has commented in his book An American Ordeal, "Thousands of people found a way to express unity beyond the divisions." The media though, tended to focus on the newly emerging counterculture in the movement, rather than on the kinds of people—evidently the majority—described by Jan Barry.

JB: Then everybody left. I started asking around, "What happened to that veterans' group?" I found out when Veterans for Peace had a meeting, went to that meeting, and I discovered that there was no Vietnam veterans' group. They initially said, "You should join us." I thought that we would make more of an impression upon people, we'd have a better ability to articulate to people what's going on in Vietnam, if we stand as a Vietnam veterans' organization. I simply started asking where any other Vietnam veterans were.

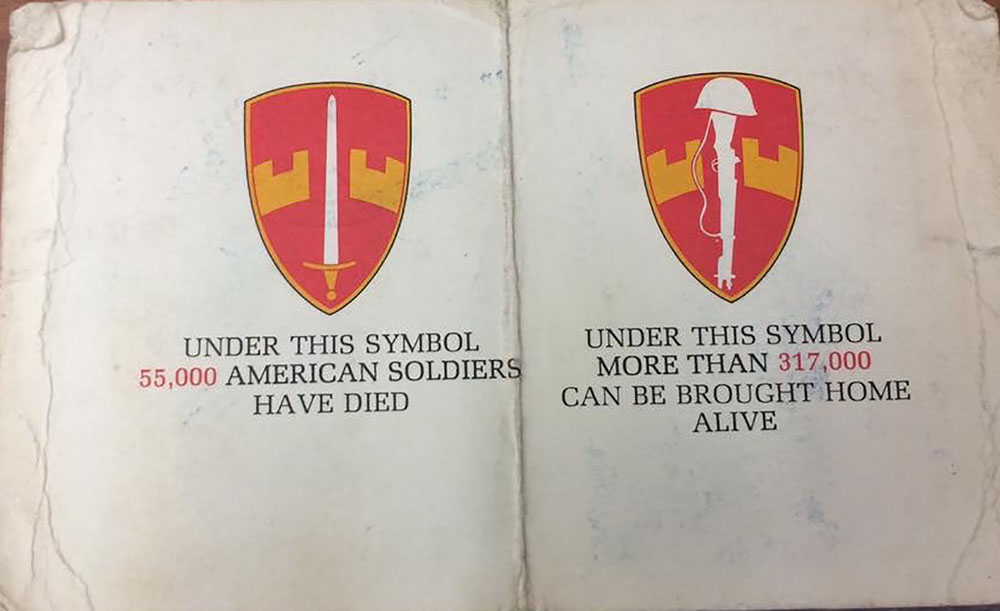

By June 1st . . . we actually had our first organization meeting. I had names of maybe two dozen people. We formed an organization utilizing the same name that was on the banner. Dave Braum designed the logo, which we talked about. "Let's take that patch that has the sword going through the Great Wall of China, and put the rifle with the helmet on it, which symbolized a dead GI. We're filling the Great Wall of China with dead GIs!" There was symbolism!

We started off with a structure that had officers and bylaws and very few people. The only titles we had were for the paperwork: president, vice president, secretary, treasurer. I didn't utilize that in most of the organizing. I would just say I was a member of the national executive committee. I did this deliberately so that somebody couldn't decide they could pop me off. I had seen a few assassinations going on. I thought, I'm not going to be a target. Somebody thinks they could just kill me and that's the end of the organization. In addition, my own sense of organizing was that these guys don't want one person telling them what to do. What they need is a process in which empowerment takes place.

One of the things that I find astounding about this whole process is, I think, that this society provides these ready-made forms of democracy that are there if you want to use them. So without even thinking about it, we formed a democratic organization rather than an autocratic organization.

Our first office was a desk in the corner of the Fifth Avenue Peace Parade Committee. We had support from Veterans for Peace. Many of us went to their meetings. They utilized their fund-raising network to raise money and get us off the ground. It was a lot of money. By 1968, we took an office of our own on Fifth Avenue.

To be continued in next issue of The Veteran

Copies of Winter Soldiers can be purchased through Haymarket Books at www.haymarketbooks.org/books/859-winter-soldiers.

|

| One of the original VVAW flyers. |