Download PDF of this full issue: v51n1.pdf (21.1 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v51n1.pdf (21.1 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=3951

Download PDF of this full issue: v51n1.pdf (21.1 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v51n1.pdf (21.1 MB) |

Details get hazy thinking about 50 years ago. 1971 was a blur of anti-war actions, organizing meetings, and writing about what should be done about ending the war in Southeast Asia. All this on top of trying to deal with some nameless condition—let us call it survivor guilt/ moral injury/ Agent Orange poisoning and other things we didn't yet know about—with insomnia, terrible nightmares and panic attacks thrown in.

Shortly after my 28th birthday that January, many of us went to Detroit, Michigan for the Winter Soldier Investigation. In a provocative approach, VVAW publicly examined war crimes through our own actions and observations as soldiers in Vietnam.

It was a harrowing experience. Many vets were freaking out in corners of the Howard Johnson's New Center Motor Lodge, where the three day event was held on January 31-February 2. The news media in Detroit was hostile to the story we wanted to tell. Radical feminists showed up to condemn us as "male chauvinist pigs." On the positive yet intimidating side, fund-raising was provided by Jane Fonda and a star-studded array of actors and entertainers including Donald Sutherland, Dick Gregory, Graham Nash, David Crosby, Barbara Dane and Phil Ochs.

|

|

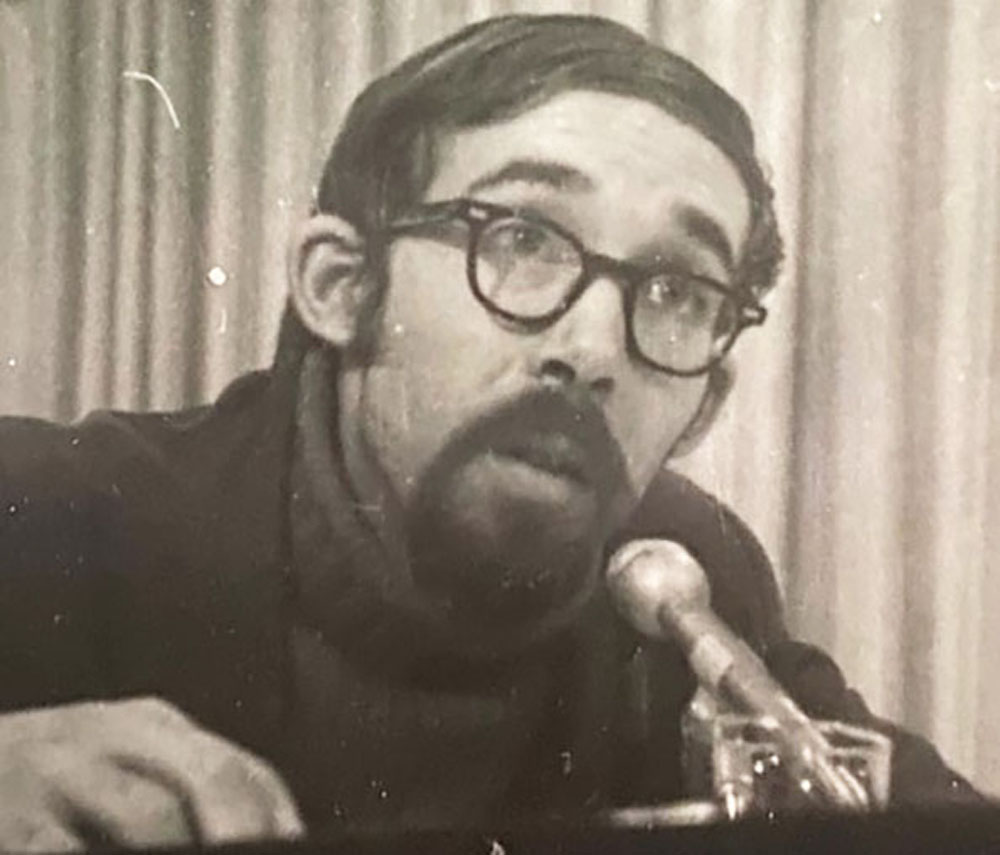

Jan Barry speaking at the Winter Soldier Investigation, Detroit, Michigan, February 1971 - photo by Sheldon Ramsdell. |

Coordinating such an historic event was way beyond my skill set as a thinly published writer and grassroots organizer. When I was elected to head VVAW in the summer of 1967, we were a tiny group of anti-war vets in New York City who'd served in the early years of the war. Many of us were there in the secretive "military advisors" period before the "big battalions" and fleets of helicopters and bombers arrived in 1965.

Launching a Vietnam veterans' group for peace in Vietnam in 1967, we talked to generally skeptical people on street corners, at college campuses, at community events, and on talk radio and TV shows about how the war was created under false pretenses. It was a long, slow slog to get more vets involved and to get serious attention from the public. We quickly learned not to talk about war crimes because Americans were convinced that Americans did not do such things.

By 1971, the My Lai Massacre had been revealed in the news. Many vets were upset that only a lowly lieutenant was held responsible for a large scale killing of civilians. Most early members of VVAW had moved on, disgusted by the glacial pace of making a dent in the public's embrace of the war. However, a bunch of vets who saw combat in big operations joined VVAW more recently and marshalled their outrage to organize the Winter Soldier Investigation.

With military efficiency, a call went out for vets willing to talk about war crimes to come to Detroit; a process was set up for interviewing these vets and seeking corroboration from documents, photos, buddies who were in the same unit; and a schedule was created for vets who served in the same division to talk on panels about actions that reflected policies—such as how prisoners of war were treated or mistreated—year after year from 1965 on.

Several vets not selected to testify on Marine or Army division panels demanded to also speak, so panels were created that addressed various other experiences, from racism in basic training to support unit actions and observations.

I co-chaired one of these panels with John Kerry, a former Navy Lt. who commanded Swift boats on Mekong Delta rivers. I felt conflicted about participating in this event. My experiences re this topic were minimal. As a radio specialist with an Army aviation unit in 1962-63 that transported MAAG and Special Forces teams on remote missions, I heard about air crews napalming villages and shooting farmers in "free fire zones." What our forum in Detroit provided was first-hand testimony from dozens of other vets that these cruel assaults were not aberrations, but perverse policy.

"We intend to show that the policies of the Americal Division which inevitably resulted in My Lai were the policies of other Army and Marine divisions as well," said former Army Lt. William Crandell, who'd served in the Americal Division as a platoon leader. "We intend to show that the war crimes in Vietnam did not start in March 1968, or in the village of Son My or with one Lieutenant William Calley….We are here to bear witness not against America, but against those policymakers who are perverting America."

Despite our best efforts to show there was a pattern to killing civilians and other atrocities by US forces in Vietnam, vets who spoke out about their experiences were appalled by the scant national news media coverage.

Yet as Andrew E. Hunt astutely noted in The Turning: A History of Vietnam Veterans Against the War: "Despite poor publicity, the Winter Soldier Investigation was successful in other respects. On a personal level, the hearings became a therapeutic event for many veterans… In addition to the hundred witnesses who testified, as many as five hundred Vietnam veterans met in the hallways and rooms of the motel to discuss VVAW's future."

A deeply etched memory all these decades later: A crowd of furious vets in a jam-packed conference room at Howard Johnson's, denouncing the news media and wrangling about what to do next. John Kerry spoke out like a bullhorn and urged us to march on Washington and take this to Congress.

Mike McKusker, a former Marine war correspondent, suggested calling the march on Washington "Dewey Canyon III," a sarcastic reference to an incursion of Laos by South Vietnamese troops as the Winter Soldier Investigation got underway, curiously called Dewey Canyon II, and a previously secret incursion into Laos by a Marine unit, called Operation Dewey Canyon, that vets testified about in Detroit.

In April, a couple thousand vets marched past the White House and set up camp on the Mall in Washington, DC under the banner of Dewey Canyon III. It was quite different from the first anti-war march I went to in Washington in October 1967. In those days, peace demonstrators were confronted by troops with rifles and bayonets. In 1971, VVAW activists found that police were reluctant to arrest this array of aggrieved war veterans. Indeed, when the US Supreme Court ruled that the VVAW encampment on the Mall was illegal, the US Park Police declined to arrest us.

Indeed, it took a defiant demonstration on the steps of the Supreme Court—demanding a ruling on the constitutionality of the war in Vietnam—to provoke the authorities to arrest 110 vets for obstructing and impeding justice. A judge later reduced the charges to disorderly conduct and released the arrestees on a 10-dollar bond.

Groups of vets fanned out and lobbied members of Congress in their offices and committee hearings. Many were rebuffed by their representatives, who lectured combat vets about the conduct of the war. My own Congressman, John Rooney (D-Brooklyn, NY) tried to bully a small delegation of vets. "I know where you stand and you know where I stand. We're on opposite sides," he shouted.

Others in Congress were supportive. A transcript of the Winter Soldier Investigation testimony was read into the Congressional Record by Senator Mark Hatfield (R-Oregon). Senator George McGovern (D-South Dakota) and others called for a congressional investigation of the war crimes charges.

John Kerry gave an electrifying speech to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee about our concerns, including war crimes, the war's death toll, the sometimes terrible care in VA hospitals, and our conviction that our troops should come home and the war should end. That he later built a distinguished political career after denouncing a once popular war was amazing.

The last day of Dewey Canyon III was beyond anything I could have imagined when VVAW was launched: Hundreds of jungle uniform-clad vets lined up and threw war medals over a crowd control fence in front of the Capitol building. Some were silent and grim as death. Others shouted to the news cameras: "Here's my merit badges for murder…I'm prouder today of the service I have given my country than at any time I was over there…I'd like to say just one thing for the people of Vietnam. I'm sorry. I hope that someday I can return to Vietnam and help rebuild that country we tore apart."

That week in Washington got the attention of Congress and the Nixon Administration, which destroyed itself trying to quash VVAW. (But that's another story.) Dewey Canyon III got daily national and international news media coverage. And an essay I wrote on Vietnam vets protesting the war appeared in The New York Times.

Clutching a treasured copy of The Times, I rushed from the dismantling of the encampment on the Mall to catch a shuttle flight to New York, wearing the grungy fatigues I wore all week, to appear on the Friday night Dick Cavett Show.

And with that, it was time to wrap up four years of often frustrating activism, to move aside for fresh, excellent leadership of VVAW and return to my previous life as a journalist. After a short stint in television, that transition led to an extensive career writing for newspapers, including an in-depth investigation of Agent Orange health issues, editing and writing books and poetry.

VVAW activism, I found, taught me how to network with people willing to share hard to find facts and how to effectively tell a true war story and other news. I learned a great many things in VVAW from fellow vets and supporters. And over the years, I came to repeatedly appreciate that among VVAW's best legacies were the lifetime friendships forged among men and women who protested together back in the day.

Jan Barry is a poet, artist, author and editor of more than a dozen books of poetry, prose and photography, including (with Larry Rottmann and Basil T. Paquet) Winning Hearts & Minds: War Poems by Vietnam Veterans. A cofounder of VVAW, he resigned from the US Military Academy after an Army tour in Vietnam. Currently, he writes and teaches about environmental issues and coordinates Warrior Writers programs for veterans and family members in New Jersey.

|

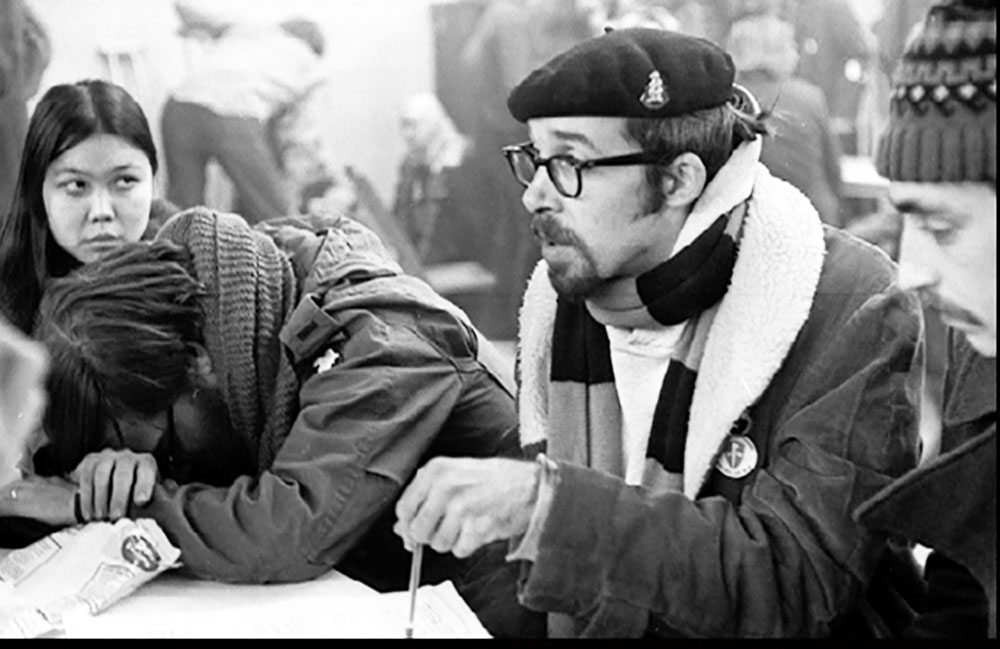

| Jan Barry at the Winter Soldier Investigation. |