Download PDF of this full issue: v51n1.pdf (21.1 MB)

Download PDF of this full issue: v51n1.pdf (21.1 MB)From Vietnam Veterans Against the War, http://www.vvaw.org/veteran/article/?id=3954

Download PDF of this full issue: v51n1.pdf (21.1 MB) Download PDF of this full issue: v51n1.pdf (21.1 MB) |

Excerpt from Winter Soldiers: An Oral History of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War by Richard Stacewicz, pages 241-249.

Interviewed are Barry Romo, Jan Barry, Bill Branson, Sheldon Ransdell, and Terry DuBose.

Vietnam veterans, dissatisfied with the lack of press coverage received by the winter soldier hearings, decided to take their stories directly to Congress. On April 18, 1971, 1,500 anti-war veterans and their supporters converged on Washington, DC, to engage in four days of protest. The following narratives describe how veterans organized the event, what they hoped to accomplish, and how they were received by their representatives and the press.

Barry Romo (BR): After Winter Soldier, I was asked if I wanted to be the organizer on the west coast. [I] came back, and they called me up and said, "We're building up this demonstration, this march on Washington; we'll pay your way out to New York." [I] flew out to New York.

[We] fought for three days [in February of 1971]. We hammered out a basis of unity for a national organization, which was really ultra-left for the time. There was infighting over what we were going to do at the demonstration. We came up there with the idea of throwing our medals away. We came up with all the stuff we were going to do ahead of time.

|

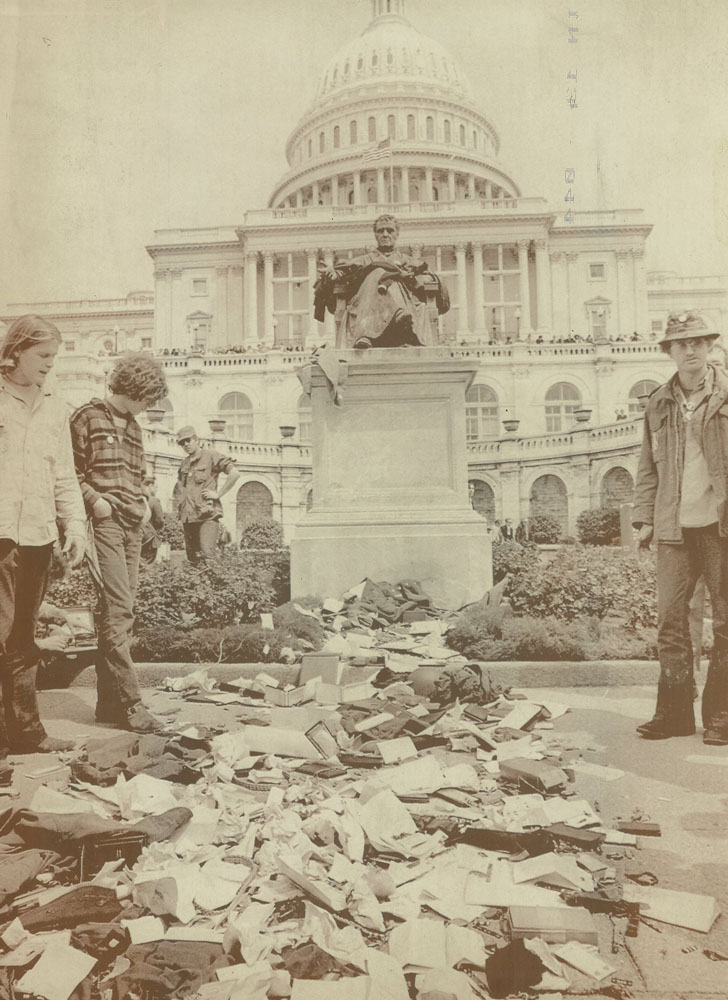

| Pile of returned medals at the end of Dewey Canyon III. |

[I] remember there was an argument for hours on what we were going to call the demonstration. As a joke, I told people, "Fuck it. Call it Dewey Canyon III. Why? Dewey Canyon I was a secret invasion of Laos, Dewey Canyon II was whatever, and Dewey Canyon III is the vets' invasion of Washington."And people said, "Hey, that's funny." It was an offhand joke. You know how you sit around a meeting drinking coffee, people have drank too much, cigarette smoke, 50 people, 50 very powerful views, and getting tired and making an offhand joke. And then, "We'll use it." People got into it. By saying Dewey Canyon, we can expose that we had a secret invasion: Dewey Canyon I. That's cool. let's do it.

Jan Barry (JB): We went from being a handful of people to doing a demonstration on the Mall in Washington that was better organized than we probably organized things in the military. For Washington in particular, there were working committees. It was a huge enterprise to do. There had to be fundraising done. There was a fund-raising committee. We went to Boston one time with John Kerry and a couple of other people to talk to somebody like Marty Peretz, who now owns the New Republic. I don't know whether he contributed or not, but we were talking to people of this caliber who put the money up for this to take place.

According to an FBI memorandum from the Washington office dated April 13, 1971, "VVAW had received fifty thousand dollars from United States Senators McGovern and Hatfield, who. . .obtained the money from an unknown New York source. " Although VVAW did receive this relatively large infusion of cash, its resources were limited and were spent predominantly on advertising the event.

JB: This guy [Kerry] was born to this. His family is part of that whole circle. I had no insight, even into this life, but I didn't put it down, while other people are saying, "Why do we have people like this in VVAW?" There were these class resentments. A lot of guys were enlisted people. "Why do we have officers being prominent?" One of the things I could get away with was, I never became an officer. I told West Point what they could do with that. Enlisted people appreciate that.

When we got to Dewey Canyon, the very first night-like a Sunday night--I got down to Washington. There were people pulling in and there was like a staging area, and some small group of people arrived from California and said something really rude and curt to me. I had no idea why they were saying that.

BR: [We] went to Washington. The national office of the headquarters where we were all coming into the first night's camp for Dewey Canyon III had a flag flying. This was like the night before we started. It was like an assembly area. We refused to register until they took the flag down. We then got the reputation as the radicals of the organization, but then a lot of people agreed with us.

Bill Branson (BB): We went to Washington—the big problem there is, we didn't have enough money to send all the people coming from California. They dicked around at the national headquarters, and we could have rented buses for all the money we spent. We could only send a few. I got to go because I had done a lot of organizing. It was my first big action.

|

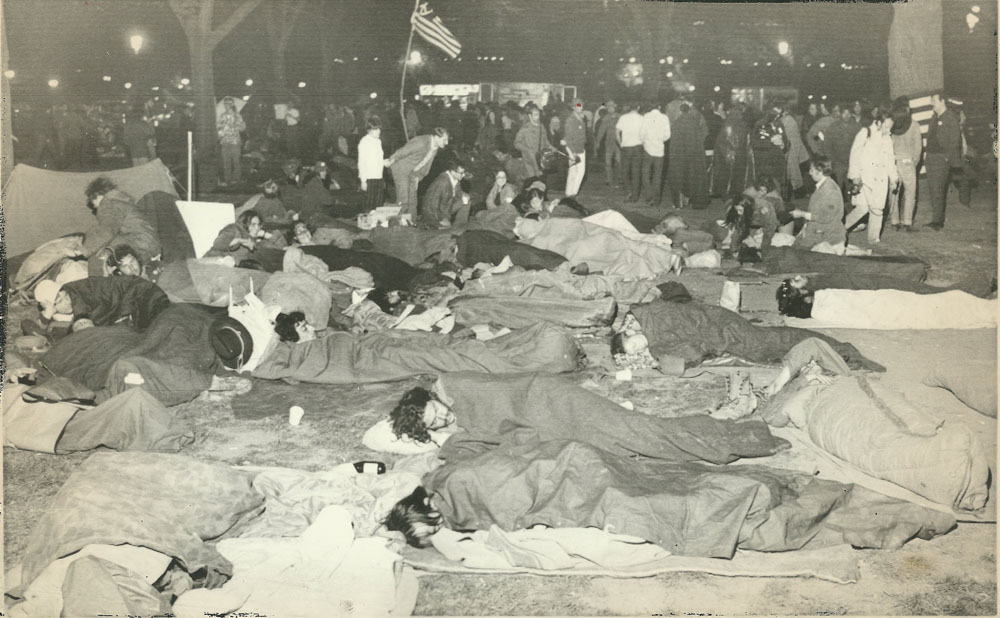

| VVAW sleeping on the Mall during Dewey Canyon III. |

We were incredibly militant. We figured if we were going to go all the way out there to Washington, to the belly of the beast, we were going to kick some ass. And we did. The leadership of the VVAW at the time. . . were from a different strata of society, like Kerry and those guys. They convinced a few people like Hubbard and others to take a conservative light on what we should do, like just basically be there and bear witness or some stupid thing. The vets who came were not in that mood.

We didn't want to tear the place apart, but we definitely wanted to make an impression. We were not there to do anything halfway. As we got together in bigger and bigger groups, we became more and more militant. The service had taught us: When you're with your comrades, you just fit right in.

When we got there, it seemed pretty damned organized. People picked us up and we got a van ride in there. At first we were on the Anacostia Flats. We weren't on the Mall. We started camping there.

We started a struggle immediately. When we got there—we were one of the first groups—there was this fucking garrison flag flying over the place, and we made them take it down. We got into quite a bit of face-to-face struggles over that, and we almost got into fights. But we weren't going to go that far. We definitely made them take that fucking flag down.

JB: We had the first mass meeting on Monday evening. Things were a little chaotic and hadn't come together as they had been organized, and everybody was milling around. We started this meeting and I started speaking. Somebody started hollering and screaming and saying nasty and rude things from the audience. Clearly this was organized to try to drown me out. I could see that there was some kind of organized business going on to try to discredit me and Hubbard and then right down the line, whoever appeared to be the leader of the moment.

So I figured the easiest tactic was to turn the meeting over to somebody else, which is what I did. I got up and sat down right in the middle of these people. The other person I left the meeting to was a little flustered, but I knew that people could pick up on this.

Some members in the Washington action wanted to move the encampment from the Anacostia Flats, relatively far from the seats of political power, to the Mall, directly in the center of the political establishment.

BB: We were supposed to be making the decision on whether we were going to fucking take over the Mall. Barry and some people were running around dragging people to this meeting where all this was being decided. There we are at this historic meeting. It turned out to be a heavy debate whether we should just go for it and whether the cops would attack us. Barry was arguing and others were arguing, "Fuck this, we're not staying here."

People had been talking about what we were going to do. There were original plans on what we were supposed to do. I don't remember what all they were, but it didn't involve taking over the Mall. It was mostly like a lobbying thing and stuff. People said, "Fuck this. We don't mind lobbying, but we're not going to sit down here near where the World War I vets were fucking slaughtered and have them do what they want to us on the side." It wasn't spontaneous; it was a decision that was made.

The next morning we took all our shit and packed it up and threw it on the trucks. We all got into this giant march. All these veterans staggered onto the road and marched up Pennsylvania Avenue. We had banners and stuff. People worked on banners all night. It was just buzz, buzz, buzz; no one got any fucking sleep. People got wired on the incredible amount of energy, pulsing energy, to the point of being manic.

|

| Dewey Canyon III, April 1971. |

It wasn't too hard to tell what we were all about. We marched up Pennsylvania Avenue and people came out everywhere. Buildings emptied; all the windows went up. I looked up and there were people everywhere. There were lots and lots of tourists there, and they were fucking cheering. We had people running out shaking hands. I had never seen a march like this.

There were cops along the sides of the street, but they stayed away from us. I can guarantee you, if they had attacked us then, there would have been guerrilla warfare in the streets. They knew better, which was good. They wouldn't have been able to stop us. Guys were not going to put up with a lot of shit.

What was the point of going to the Mall?

BB: I was for anything that was going to kick ass. I really didn't care what it was. I wasn't going to set anything on fire. Short of that, I was there to make an impression. I felt like Washington was full of assholes that sent us there and I was prepared to spit in their eye, amongst other things. I didn't have a highly developed line on propaganda, but all of us instinctively knew that we were in a historical situation. We talked about it a lot. We were there to do as much as we could. We weren't going to be told to be good boys and go home.

Was the discussion the night before causing tension between the national office and different people around the country, or was it pretty much consensus and everyone agreed after the decision and every one went along with it?

BB: I think as it became apparent that it was the right thing to do, they went along with it. They couldn't have done otherwise.

There was a definite force from the national to tone things down. Constantly. In fact, they tried to gather all our plastic guns and we said, "No, you're not." "Oh, no, you're going to get us shot at." "No, we're not. If they shoot at us, the world won't end tomorrow."

They were trying to get us to be conservative, and it just wasn't getting over. Your average guys there felt like they had been shafted. All those people had already had a chance to be fucked by the conservative people who were still in charge of society here that treated us as outcasts and shit. They had no jobs. We felt an intense kinship with the people still in Vietnam. We felt the war was wrong and it was going to go on forever if we didn't do something about it ourselves. It was time for us to make a statement. We made it in our typical fashion. We tended to be almost instinctively organized in everything that we did. We didn't take any shit, and we were smart in almost everything that we did. We were not conservative, so we got in arguments constantly with the leadership. I think almost immediately, as we started pouring in, they got scared.

I think they were afraid of us. I remember getting in a shouting match with Hubbard. He's telling us a lot of bullshit—that if you act this way you're going to get thrown out. We're telling him, "Fuck you, you're a jerk-off, why the fuck won't you talk to us like human beings, we're not fucking kids, we're part of this thing, you ain't shit, and who elected you anyway?"

JB: I stayed pretty much on the site. I went with Kerry on one occasion to the State Department. We gave a briefing to State Department people in a briefing room. It blew my mind. They wanted to know why we were there! We had a list of demands that I read on the steps of Congress which in essence became a legislative model for several different things that were proposed in the following years, pointed toward the VA and various other directions.

Then it was like getting us through a week in which a lot of improvising went on. Something came up, like they refused to allow the group into the cemetery the first day. I had nothing to do with the decision that was made. Somebody, whatever number it was, decided that the solution was to go to the Pentagon and offer to turn themselves in as war criminals, which blew the Pentagon's mind. "What do we do with these people? We'd better let them into the cemetery."

BB: A bunch of guys from California went down to the Pentagon and tried to turn in a bunch of guys as war criminals. We took over everything—the Lincoln Memorial, the Rotunda—we walked in the streets. Nobody stopped us.

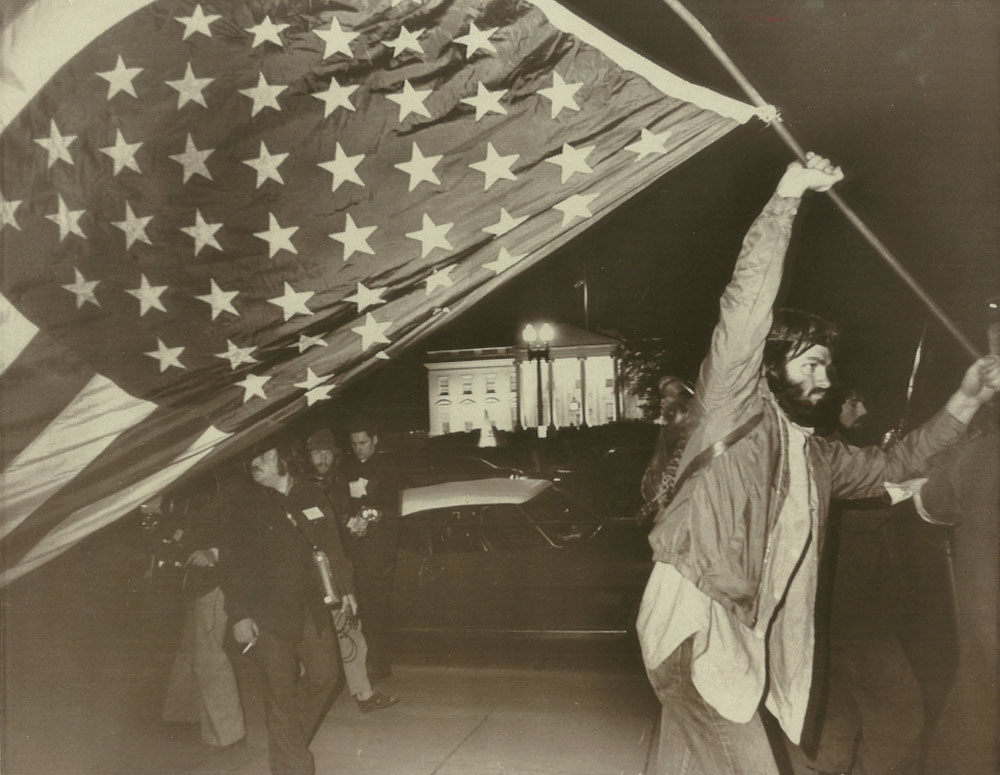

JB: When Nixon was quoted as saying he didn't think these were real Vietnam veterans, one group decided they were going to go parade at night around the White House with the flag upside down. It was tremendously dramatic.

Sheldon Ramsdell (SR): Ron Ziegler had said, from Nixon, that this was just a bunch of hippies. A woman came down to the Mall from the AP or UPI, [and] collected nearly 1,000 combat cards—you know, military service cards (DD-214s). She put that in the paper the next day. Nixon was totally discredited.

Terry DuBose (TDB): It was exhilarating. Incredible camaraderie. They had these tables with food laid out from people in the community. You could have anything you wanted. We all wore our fatigues, and if you went out on the curb and stuck your thumb out, a taxi would pick you up and take you where you wanted to go for free. They were all sympathetic.

Did you lobby?

BR: We lobbied; all of us lobbied. I didn't believe in lobbying at this point. I thought they [elected officials] were all scum. They would only move when we forced them to move. But we were going to lobby, so we went lobbying. We went and saw our congressmen and stuff. We decided lobbying just wasn't enough. It just wasn't dramatic enough.

We got up one morning and sat in at the Supreme Court. That wasn't planned. Some of the national people got mad: Mike Oliver, Jan Barry, Scott Moore, and Al Hubbard said, "You're going to ruin the demonstration by doing this." We said, "No, we're not." We got arrested and it made great news. Rather than be a detriment, it was good. The media loved it.

Why do these kinds of media-grabbing events?

BR: They [the American public] saw the war on TV. They had to see us on TV. People's experience was not being in a rice paddy, but watching someone in a rice paddy. We had to interrupt their seeing war on TV with their seeing veterans demonstrating against the war on TV. We had to fucking interfere with their fucking lines of thoughts, and that was the only way to do it. We know, and they don't. We're telling you that what you see on TV is not it. It's part of it, but it's not it, and it's wrong and you've got to bring people home.

After the veterans decided to move their encampment, Justice Warren Burger upheld an order by the Justice Department that they were to be removed from the Mall at night. They were told that they would not be allowed to sleep in the park at night; it was illegal. One of the most critical debates among veterans took place as a result of this ruling.

BR: We came back [from the Supreme Court), and the Department of Justice said we can't go to sleep in the park. I think it was Mike Oliver [who] got up and made a speech: "We won't sleep; we won't break the law. We're going to stay here and demonstrate till the end of the week; we'll take speed to stay awake so they can't arrest us; we'll stay awake for the next three days." One of the guys, Sam Schorr from California, got up, and he said, "These guys are crazy. One, no one told us where we could sleep in Vietnam. Two, ain't nobody going to tell us as Vietnam vets that we can't sleep in our park. Fuck them. We are going to sleep in the park. If they're going to arrest us, they'll arrest us. We're not going to take drugs, drugs are destroying the country." People went back and had heartfelt discussions, and we won the vote. The overwhelming majority of people who lost the vote stayed, even though they didn't want to get arrested.

JB: It was a huge discussion. It was a close vote, which everybody had sort of pushed aside. It was like 480 to 400 [to stay]. I had a telephone line to the outside so I could call and say, We're now being arrested. It was a special line that had been put in so they could round up all the lawyers and the rest of it. I'm sitting there on a camp stool, and I think it's Urgo that came up and said, "Well, what are you going to do if they [the park police] come in?" I said, "I'm just going to stay."

I was torn. I was always a very conservative person when it came to tweaking the nose of the law. I saw no purpose in spending any time in jail whatsoever. I thought it was lost time, number one. Civil disobedience was a tactic to me and not a lifestyle. For a lot of people, it was their life. You do this and to hell with whether or not you accomplish anything, but you feel good. I wanted to know what we were accomplishing. I mean, what's the purpose of going to jail?

We [also] have a right to be here on this place, camping. They can't just arbitrarily take this right away from us. But there was this debate, which Kerry and Hubbard led, where people stood up in the crowd and argued this and that side of it, and then they voted. It was real democracy in action. It was astounding. Once the vote went 480 to stay, then the consensus was: Well, if you're staying, then I'm staying.

BR: We got our sleeping bags out, supremely confident that we were going to get arrested, smiles on our faces. [We] got into our sleeping bags—we hadn't been sleeping in them before-got in them because, by God, we were going to sleep there.

I remember Ron Dellums came to our delegation because he was a California congressman; [he] wore his medals. Ron Dellums stayed with our contingent overnight and said that if they arrest you, they're arresting me. They're not arresting me as a congressman but as a veteran. We loved the man. No publicity here. "I'm here, I go to jail with you."

JB: Edward Kennedy was there most of that night in a tent talking with veterans. You never knew who you were going to run into. I turn around and bump into somebody who's a member of Congress.

BR: We're in the bags; the park police start walking through and they looked down at us. This lieutenant or captain, this old chubby white guy, looks down at us and goes, "I don't see anybody sleeping. [Laughs.] Nobody sleeping here. You guys don't have to worry about nothing because we don't see anything and we're not going to do anything." So we all laughed. And Dellums stayed until about two in the morning and said, "Well, they aren't going to bust, so I'm going to go home." We said that's all right. He was there.

We got up in the morning and we beat them. That made it "Vets Overrule the Supreme Court." It was a crisis in the national government, with Burger convinced that this was a communist march on Washington. He was the one that ordered us to be arrested on the Supreme Court steps, and the other justices are going, "What are you doing?" If you read The Brethren [by Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong, 1979], you read how all the other Supreme Court justices think Burger has gone butt-fuck. This guy was having flashbacks to: MacArthur was right when he killed the Bonus Marchers. He wanted us killed and driven out of the city. He thought that was so just.

Despite the efforts by the Nixon administration to have the veterans evicted from the Mall—with which the Supreme Court had cooperated—John Dean sent out a directive ordering the park police not to arrest veterans. At this point, Nixon's aides did not want a confrontation that would arouse public sympathy for the veterans, who had been receiving a great deal of media attention. The veterans, however, did not know of this directive.

JB: The original intent of the Friday (event) was to take all the medals and throw them into a body bag and to take the body bag to the Capitol. People got mad because they put this fence across the steps of Congress. "What are they putting this up for? It's fencing us out." So on the spot, there was this mumbling and grumbling, and someone said, "Let's throw the medals over the goddamned fence."

BR: Getting ready to throw our medals away, [there] was a fight with Kerry. Kerry wanted us to put them in a body bag. [Kerry argued] that it would be disrespectful to throw them away; people wouldn't understand. That was the only fight I ever remember having with Kerry. I said, "Fuck you. God damn it, we decided this months before; at every point you want to change shit. The only way we're going to wake the public up is to do dramatic events, and we got these medals. . . We're making a statement that they can't ignore," and stuff like that. People handily decided to throw their medals away. I don't think Kerry did. Then we went and lined up and just threw the medals away. [It was] one of the heaviest things.

On April 23, 1971, about 700 veterans and their supporters gathered outside the fence erected by the Nixon administration at the west steps of the Capitol. They lined up, approached the fence one by one, and announced their names and ranks and the awards they had received while serving their country. They then threw their medals over the fence—back to those who had conferred these honors on them.

JB: After we had really reached a peak, we heard there were also soldiers on active duty ready to be sent in to do whatever they were ordered to do, as in the 1932 march. There was a big story in the Washington papers, recalling all those events in which they turned soldiers on their own companions of World War I. One of those evenings, this young guy arrives in the middle of the camp and says, "I'm from the 82nd Airborne" or something. He said, "They order us to come in here, we're not coming. You guys are our only hope that we don't have to get sent to Vietnam, or back to Vietnam." We got pieces of that kind of information all week long, plus this overwhelming support of people just coming with food, and money, and donations.

It [Dewey Canyon III] was overwhelmingly successful in several different ways. We had the five o'clock follies, which was our take on press conferences in Vietnam. These news media people lapped this all up, because we did this parody of a military news conference. One of those evenings, at five o'clock, this guy comes over to me, hands me this thing, and he says, "This is what Walter Cronkite is going to be reading tonight at six o'clock." It was very positive and made this a major nationwide and international news story, because the Cronk was it. Cronk says, Take notice of this, America. This was the guy who had written what the Cronk was to read, and he rushed over there to hand it to us. At that point, I knew that the White House had lost the public on this issue.

There was a Time magazine retrospective that said this was probably the most memorable or most important demonstration of the peace movement. Everybody had forgotten that that kind of statement was made about it. But I think that it had that effect because the peace movement by this time was exhausted.

SR: CBS had a truck down there. Cronkite has us on every single night. We had a logo [VVAW insignia] on the back of his head every single night for the rest of that week. It all changed, just like that. Look how far we had to go to get any kind of credibility at all. A reporter from a news service collected our cards, and suddenly we're real. What the hell's been going on all this time? Nobody's been wanting to believe it!

JB: At some point after that, I did get some feedback from a friend of mine who still was in the military as an officer. He said that in the Pentagon, VVAW's demonstration shook the whole place up. Captains and majors were screaming at colonels and generals that they better fucking wake up: "Those veterans out there were right." People who did two or three tours were not going to go back again to save the assholes of these people who screwed it all up. It set off within the military establishment, apparently, this vicious debate.

What impact did Dewey Canyon III have on the organization?

JB: There were groups that came out of this that decided that what they wanted to work on was the legislative aspect of making things happen. Other groups decided what they wanted to work on was the psychological—what became the rap group direction. Other groups decided they wanted to work on community organizing when they went back to where they were going back to. Other people decided that what they were going to do was to go back into the academic world, get that degree that gave you the credentials; and they went and did that. Other people, like John Kerry, decided that politics was where they wanted to go. They went there and they got there.

They turned mainly conservative guys into radicals overnight with the way the government reacted. These guys came here thinking they were going to talk to their congressman and be listened to. That was the original intention. We'd go to Congress and lobby them like everybody else does and get listened to. When they slammed doors in our faces and threatened us everyplace we turned, these guys got radicalized.

Copies of Winter Soldiers can be purchased through Haymarket Books at www.haymarketbooks.org/books/859-winter-soldiers.

|

| Dewey Canyon III, April 1971. |

|

| Dewey Canyon III, April 1971. |

|

| Dewey Canyon III, April 1971. |