|

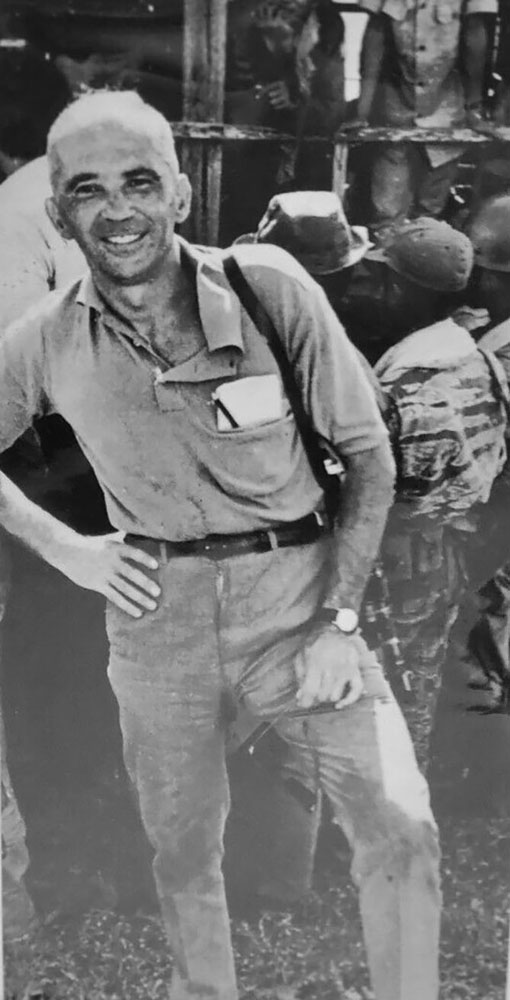

Cornelius Hawkridge ObituaryBy John KetwigI am sad to report the passing of Cornelius Hawkridge, who I consider to be one of the few true heroes of our American war in Vietnam. Mr. Hawkridge was 95 years old, and a resident in an assisted living facility in Missouri. He was somewhat of a recluse, a fugitive from his past, but he was also my friend. A book, The Greedy War by James Hamilton-Paterson, tells Hawkridge's story. I consider The Greedy War (British title A Very Personal War) to be the best book I've ever found about the war in Vietnam. It took me a long time to find a copy, back in the days before the internet. Time after time, used bookstores that offered search services would try for weeks or months, and ultimately tell me, "It's suppressed. There are certain books the government doesn't want you to read, and they disappear. I'm sorry, but I can't find one." I found it hard to believe in "the land of the free" where freedom of the press is at the very top of the Bill of Rights. I finally found one in a used bookstore! I guarded that book like it was gold. And, I began to look for Cornelius Hawkridge. I wanted to shake his hand and thank him for what he had done. Hawkridge was British, but he grew up in Hungary. After World War II, Hungary found itself behind the "Iron Curtain," dominated by the Soviet Union. As tensions increased, Hawkridge took part in acts of rebellion against the Soviets and was sentenced to life in a gulag coal mine. One day, for reasons he never discovered, he was released. He returned to Budapest, where the Hungarian revolution was raging, and one morning he saw a Russian tank rumbling into the neighborhood. Hawkridge escaped to Austria on foot, where the CIA interviewed him about the gulags, and in appreciation, they flew him to the US. He found employment with a security firm involved in the occupation in the Dominican Republic. He was deeply troubled when he saw the government officials living in great luxury while the common people were penniless and mistreated. Many of the items designated for the poor, including food, were instead diverted to the black market. One of Hawkridge's co-workers noted his hatred for communism and suggested he investigate the company's operations in Vietnam, working alongside the American military. If he transferred there, he would join the forces opposing communism, and he would earn significantly more. The Vietnamese had learned to steal the enormous wealth Americans brought to their impoverished country. For instance, by law, all cargo had to be unloaded from ships and planes by Vietnamese stevedores. From his very first days in-country, Hawkridge heard complaints that up to 80% of all the goods loaded onto trucks and transported to their American military destinations never arrived. He investigated and saw whole convoys detouring and unloading their cargoes downtown. When he reported this, he was told to look the other way. He even managed to meet General Westmoreland, who told him, "You have an opportunity to become a rich man. Shut up, play along, and you will get rich. Don't make waves." Hawkridge was appalled, and he began contacting Congressmen and Senators. On a trip back home to the States, he was driving on a mountain road when a truck pulled alongside and forced him off the road. His wife was killed, and Hawkridge spent months in a wheelchair. He was invited to testify before the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations, chaired by Senator Abraham Ribicoff. From his wheelchair, Hawkridge described the corruption happening in Vietnam, the money-changing, and the military's obvious participation in it. Surprisingly, he was not allowed to talk about the loss of goods to the black market or the enemy. In mid-July of 1969, Life magazine did an article revealing not only his testimony but also his great distress over the theft of goods shipped to our military. That was supposed to be the cover story that week, until Ted Kennedy drove a Buick off a bridge in Chappaquiddick, Massachusetts. I was determined to meet Cornelius Hawkridge and shake his hand. I wrote to the publisher of The Greedy War, and months later they informed me that they couldn't be of any assistance. I found a recent novel by James Hamilton-Paterson and wrote to him. More months went by, as I learned that Paterson lives half of each year in a grass hut in the Philippines and the other half in Tuscany. (He says he cannot write about modern civilization while participating in it, so he does most of his writing in the Philippines.) After a long wait, he responded to my inquiry, providing a few names of people Hawkridge considered friends. He warned that Hawkridge was intensely private, as he believed sinister forces were still trying to kill him. One of the names Paterson suggested was a writer for Time-Life, who had done the Life magazine article. I managed to connect with that writer by phone, and he flatly denied that he had written it, or that he knew anything about Cornelius Hawkridge. Finally, I contacted a retired Air Force officer in Texas, and his wife offered to contact Hawkridge to see if she could provide his address or phone number. He called me one evening, and we had a long and spirited conversation. I had spent 7½ years trying to find him. At that point, I was working, and traveling constantly, and Cornelius was far more inclined to write, so we exchanged letters. He typed and was always very open about his Southeast Asia experiences. For a long time, we talked on the phone about once a month. I think it was about 2003 that my wife and I planned a vacation trip and spent a couple of days visiting his farm. Once we got past the dilapidated guard shack at the gate, I finally got to shake his hand and we talked for hours about his adventures. We got on well, and I regularly talked with him by telephone. His advancing age became a factor, as he could no longer type letters, and his hearing deteriorated to the point where I would have to shout into the phone. Since retiring, we have visited about once a year. Cornelius was a voracious reader. I combed through used bookstores for the types of non-fiction he liked, and sent them often, by the box load, by media mail. Then, a couple of years ago, it became necessary to move him to an assisted living home, and he refused to talk on the phone from there. He enjoyed letters, and Carolynn and I both wrote to him, adjusting our printer to produce big, dark print. We saw him last October, he was 95 years old and frail, and he passed away on November 6th. That was less than three weeks after our final visit. Cornelius Hawkridge was a recluse, believing to his dying day that agents of the old KGB were looking for him, intending to kill him. I was careful to maintain his privacy. He was a rigid man, in the old-world European manner. He never smoked, never tried any form of alcohol, and never used any profanity. A Great Pyrenees dog was his only companion. His one great appetite was for cheesecake, and we sent him large assortments of cheesecakes every year for his birthday and Christmas. He seemed to enjoy our visits when we would "chew the fat," most often about the corruption he had seen in Vietnam, his efforts to do something about it, and the deteriorating world situation. Cornelius Hawkridge was a genuine hero of the Vietnam War, but he could have done so much more if anyone had listened to him. The truth about the war was carefully and systematically covered up or ignored in those days, amid widespread corruption and profiteering. Over more than thirty years, I learned to love Cornelius Hawkridge as a good, simple, honest man who attempted to expose the disgusting truth about America's way of waging war. I hope he is resting in peace now. John Ketwig is a lifetime member of VVAW, and the author of two critically-acclaimed books about Vietnam, ?and a hard rain fell and Vietnam Reconsidered: The War, the Times, and Why They Matter.

|