|

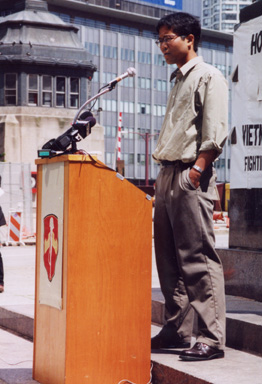

Blessings and ResponsibilitiesBy Jack SurisookSpeech from VVAW Memorial Day event, May 28, 2001 I'd like to begin with a quote by Mr. Barry Romo. "Someone once said, 'How could you change so quickly?' I said, 'Well, it wasn't a question of changing quickly; it was a question of being in shock over taking the blinders off. When you take sunglasses off, the sun shines in: it doesn't trickle in, it doesn't take time, it all becomes bright.' That's the same thing that happens once you get rid of the mythology that chains you down. You can see things because you're free." About two years ago I was sitting on a street in Bangkok flipping through the Bangkok Post when I came across the story of Rachel Goldwyn, a 28-year-old pro-democracy activist who had been arrested, tried, and convicted in Rangoon, Burma for chaining herself to a lamppost and shouting out pro-democracy slogans. The judged sentenced her to seven years in prison with labor. There was a picture of her, smiling, blond curly locks, wearing a shirt that had the face of the sun on it. She was the daughter of a London TV producer and had told her parents she was going on holiday to Germany. Staring at her photo I became haunted and disturbed, picturing her next seven years in prison. It seemed an alien proposal to me. What had caused her to fly thousands of miles to speak out for the rights of the people of a poor, distant country? Some might question her method, but no one could question her sacrifice. I have kept that article since that day and the two years since then her actions have informed my life. Her sacrifice highlights the blessings and responsibilities we have as Americans to exercise the tools of our democracy. I also learned from the selfless way she must have viewed the world. Her vision transcended national boundaries and she realized that oppression in Burma was a blot on all of us. They weren't just poor distant Burmese, but people who deserve the rights that we here often take for granted. That selflessness is also seen in someone like Sister Carolina, a Franciscan nun who works tirelessly to educate people around the world about the tragedy that is occurring in Colombia, to enlighten Americans about the atrocities, the forced displacement from homes, that are occurring as a result of our "drug war." What's going on in Colombia needs to be known. Under the moral umbrella of this drug war, the United States is sending a billion dollars of military aid into a country that has had a recent history of violence and human rights violations. The issue of Colombia is a difficult one to understand and calls for a measure of vigor and patience. Its strategic geography and wealth in natural resources makes it valuable to U.S. and corporate interests. The suggestion has been broached that Colombia has all the earmarks of another Vietnam. One doesn't want to jump to hasty conclusions, but the ripple effect of Plan Colombia is already being felt. In Wednesday's Wall Street Journal there was a story about the president of Venezuela, Hugo Chavez's interest in purchasing Cobra attack helicopters from Bell Helicopters, the same makers of the Huey II helicopters being provided as a part of Plan Colombia. This interest in offensive military hardware by Venezuela is in direct response to the military buildup in Colombia as a result of Plan Colombia.

The crops of farmers in the Putomayo region are also being destroyed: 3000 acres of bananas, 9000 acres of pasture and 1300 acres of yucca, according to a police report filed by farmers. Hunger in that region has also become a growing problem. There has been movement across the border into Ecuador, perhaps the least-equipped country to deal with refugees, itself being in turmoil and suffering from the worst inflation in the Western hemisphere. It has been said that if Colombia is Vietnam, then Ecuador is Cambodia. In the past week there have been bombings in Bogota and Medellin leaving twelve dead and over 150 injured, causing fear that the fighting between the paramilitaries and the guerrillas is moving into the urban areas. This has happened as Colombia's Senate is debating measures that would be tantamount to declaring a state of war by allowing broad power to the military to arrest people without warrants and to suspend already weak human rights requirements. With the new Andean Aid package proposed by Bush, military aid in the guise of drug war funding would be extended into the whole region, including Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela and Bolivia, broadening the reach of U.S. military influence.

We are seeing the outsourcing of military functions to private military corporations. We have seen the establishment of strategic military locations surrounding Colombia: Curaçao in the Caribbean, Manta off the coast of Ecuador, and Iquitos in the Peruvian Amazon. We are seeing the repeated spraying of a broad spectrum herbicide, a herbicide that the United States insists is safe, but is the third leading complaint of farm workers in California, a herbicide so corrosive that it cannot be stored in galvanized steel containers, a herbicide doing a good job of denuding everything except the coca plants. We are seeing the violence spill over into poor neighboring countries which are, to say the least, politically unstable, and we are beginning to see a desire for an offensive military buildup in neighboring countries as a response to Plan Colombia. The parallels are obvious to any student of history. The question now before us is whether we as Americans have learned anything from Vietnam. If we as a country have only learned counterinsurgency tactics, press bans by the military, and the outsourcing of military functions to private companies as a way of washing our hands, then my contention is that we've failed. We've failed to advance our country toward any notion of a more humane future, but rather have only developed more surreptitious and deviant ways to wage war. But if we choose to learn from the men and women of VVAW, if we have gained a voice that matches our conviction, if we are not resigned to apathetic impotence, if we are engaged in curious and critical questioning of what our government is doing in the name of the American people, if we have the courage to remove the blinders and stare directly into the sun then I feel we would most honor the sacrifices of the veterans of this country, we would honor the memory of men like Jack McCloskey, we would do justice to the work of Sister Carolina and Ignacio Gomez and Jineth Bedoya. Men and women with the courage to have compassion. Men and women who believe in the power of choices and actions. When history is viewed as a collection of choices which define action, that empowers our present. When Agent Orange was finally somewhat acknowledged by our government and brought out into the public consciousness, it wasn't because it was a preordained excerpt from some all-encompassing historical tome. Rather it was the struggle of men and women of the VVAW who saw the truth of what was happening to the combat veterans who had returned home. The fight was fought measure by measure by people dedicated to social justice, dedicated to the rights of the veterans who had sacrificed so much of themselves for this country. VVAW has shown us the power of educating, has shown us that to actively pursue change, people need to inform others of the truth of what is going on. One month ago some of the students of Richard Stacewicz's class organized a forum, a teach-in to inform others about the truth of what is happening in Colombia. The speakers included Barry Romo, Leslie Coombs, and Pastor Andrew Ullmann from Witness for Peace. The discussion lasted for almost two hours and was attended by approximately 120 people. We didn't move mountains, but what we did was create a little ripple, a brick in the foundation for change. Hopefully dedicated people across the country will have the conviction to transform the multitude of ripples into a wave. The voice for change and social justice is not limited to separate struggles, but is like gossamer that transcends space and time. A continuum of people who refuse to live on blind faith alone and who challenge humans to embrace their humanity. The memory of veterans is not honored by glossed-over and contrived blockbuster movies that cloak themselves in vicarious patriotism. The memory of those men and women deserve more. They deserve that posterity will work to spare their sons and daughters the terrible toll extracted from them.

|

In last Sunday's Chicago Tribune one U.S. official was quoted as describing the fumigation of coca plants in the province of Putomayo as being a "war of attrition," acknowledging that the farmers would simply return to plant the highly resistant and highly profitable coca plants amidst the wasteland of dead foliage. The words "war of attrition" being used to describe the entanglement in a tropical developing country has an eerie, déjà vu quality.

In last Sunday's Chicago Tribune one U.S. official was quoted as describing the fumigation of coca plants in the province of Putomayo as being a "war of attrition," acknowledging that the farmers would simply return to plant the highly resistant and highly profitable coca plants amidst the wasteland of dead foliage. The words "war of attrition" being used to describe the entanglement in a tropical developing country has an eerie, déjà vu quality. So what we have here is a developing country with difficult tropical terrain that has seen many years of fighting between the military, paramilitary, and guerrilla forces. To that mix the United States has sent military advisors to train the government troops and an infusion of a billion in military hardware including Blackhawk and Huey helicopters.

So what we have here is a developing country with difficult tropical terrain that has seen many years of fighting between the military, paramilitary, and guerrilla forces. To that mix the United States has sent military advisors to train the government troops and an infusion of a billion in military hardware including Blackhawk and Huey helicopters.